The vagrant pleasures of superior prose

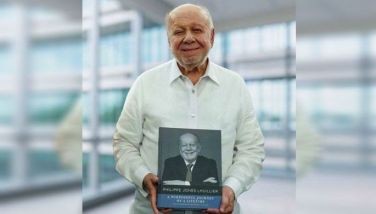

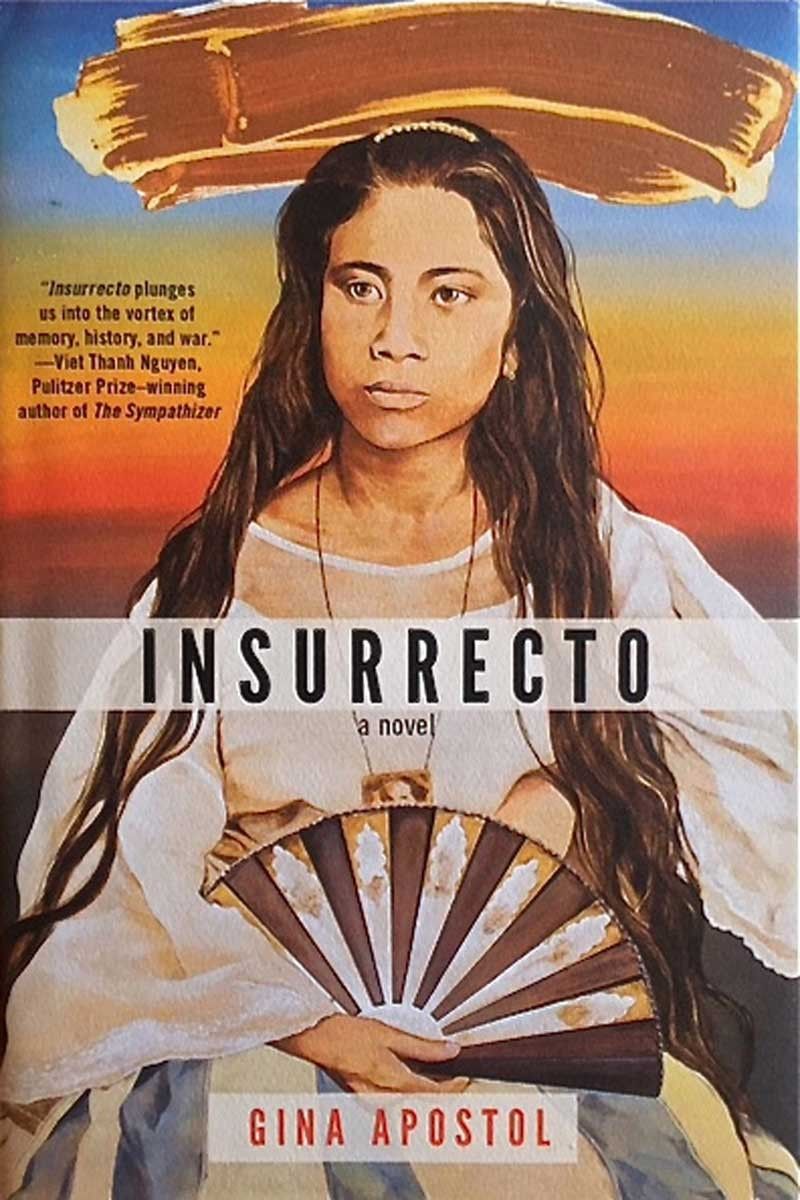

Undoubtedly a master of prose, Gina Apostol confirms this further with her fourth novel, Insurrecto, published by Soho Press of New York, and generating rave reviews thus far. Unmistakably, the book teems with extravagant instances of writing that are memorable for literary flair.

But it’s not just that flair, or panache, that distinguishes Apostol’s superior quality as an author. Overwhelming evidence of erudition is also displayed on every page. Literary, academic, cultural, experiential and online “woke”-fulness is brandished; I wouldn’t say fiercely, but it’s not entirely subtle either, rather much like second nature as a PoMo feature.

Littérateurs may nod, swoon or gasp over her audacious turns of passage, which are like multi-level access and egress points through a cloverleaf flyover that leads to sundry highways. Back and forth, that is. Supreme intelligence is at work, from the narrative engineering standpoint. But what may be deemed precious is the ludic creativity. If one’s mindset is equipped to find it.

As a narrative, it often sparkles with memorably architected characters. Chiara is an indie filmmaker who takes after her father Ludo Brasi, who directed the cult classic The Unintended, rival to Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. She returns to the Philippines with a script in mind that might dwell on the Balangiga massacre.

She meets up with the lady translator Magsalin, who accompanies Chiara to Samar, but engages her in a scriptwriting duel. Their discourse: whether a translator has the right to invade original work. We can tell on whose side the author is, as one of the theses in the episodic narrative is the colonizer’s absent or aborted right to history.

A century earlier, another lady, the well-connected stereographic photographer Cassandra Chase, catches up with the ill-fated Company C of “americanos” stationed in Balangiga. Cassandra castigates her fellow colonizers for their hamletting ways. She becomes a houseguest of Casiana Nacionales, the eventual “Geronima of Balangiga” who signals the start of the breakfast attack by the natives upon the tolling of bells. Cassandra in turn testifies before American authorities when the “howling wilderness” counter-massacre is investigated.

The only notable male character, if in a cameo role, is the town chief:

“That bumbling oaf, that mumbling linguist, that chess nut and arnis grandstanding master, Valeriano Abanador, the Chief — what an actor! He had tricked them all with his sheepish ways for two whole months. He came howling with his sundang in one hand, in the other a bolo, to lead them, a thousand strong, bands of men headed for their jobs — men to hack at the barracks, men to hack at the mess hall, and the best men to go after the officers in the kumbento. They hacked them, hacked them, hacked them.”

The individual backstories are an encyclopedia of effective research, done online or in libraries, or experienced first-hand in Europe, the USA, and Magsalin’s home country. But the back and forth between time zones and mise en scénes, between the staggered exposition and constant philosophical musings on art, culture, and film appreciation, can make it a tough read. It occasionally turns dense, given the unremitting disruptions by dint of sly authorial omnipotence.

At some point, the author states, almost as a challenge: “A reader does not need to know everything.” True. But the conspiratorial POV often winks at us, the readers. We are caught in a loop. It’s what makes Magsalin’s uncles, long transported from Samar to Manila, charming characters, as masters of karaoke. For Magsalin is the author herself.

Her progressive Big Apple ken allows her to use “agency” as a social science term, along with “invidia” (empathy), “diplopia,” “amphisbaena spines,” “reflexive signifiers,” “scudetto,” and “affective fallacy.” While distaste is expressed for the word “praxis,” Pinoy words are all over the pages, un-italicized, leaving foreign readers the option of Googling exotic terms from “butaka” to “butanding,” “saba” to “sundang.”

Often it reads like a puzzle, the locked puzzle that is one of several literary motifs in the story, like the void and the sweating beast, the Borgesian dream, the Ali and Elvis hagiography.

But when the writer relies primarily on the strength of her expository voice, prolifically parenthetical passages thankfully give way to epigrammatic lines equal to hard poetry. As with “desire’s prongs.” Or this: “Her brain was a ball of hair in a bath drain, as miserably dense as it was inert. A mess.”

Another prose jewel:

“Who has jurisdiction if a mere slip of a woman in a billowing silk gown completely inappropriate to the weather and her situation flouts the general’s orders in Tacloban and manages the journey across the strait and down the river anyway on her own steam, with her diplopia and diplomatic immunity intact, a spiral of lace in her wake, a wavering tassel of white, complete with trunks full of cameras and Zeiss lenses and glass plates for her demoniacial, duplicitous photographic prints?”

Maybe this is such treasure that it is repeated in a subsequent sub-chapter. Or it’s another PoMo trick, as are the deliberately misnumbered or missing sections

My favorite expository passage in Insurrecto describes, and possesses, Chiara’s mother Virginie:

“When she wakes up, her hand is still on her body, a warmth pervades her in the hotel in Hong Kong, despite the ice. The minute she had left Ludo out there in Pampanga, or Makati, or wherever it was he happened to be after The Unintended — the minute she left him, she missed him. In the dream, she does not know if she is coming in the dream or in her hands, and in this way, it seems, the moment of her coming goes on in infinity. Arousal for her is like this. She comes several times in her hands, and she comes several times in her dream, and it is an oddly comforting kind of vertigo, this chain, this superior sleep a woman can have, she thinks, the potential for multiple orgasms suggests that the superior sleep a woman can have lies in the possibility of orgasmic infinity, her eternal arousal, she is moving her hands over her body, her vibrant cunt, the way a vagina kind of buzzes, a tender undulant thing, so alert, so alive. This vagrant pleasure, controlled by her own hands. In the dream, she recognizes she is in a dream. She can feel the dream of her desire and its consequences reverberating, a concatenation, this infinity — the way she orgasms, a multiple chain of arousals, and it doesn’t matter anymore whether it’s dream or reality; her body is convulsing, warm and powerful and hers, she is depleted and sated, she shakes to her hands’ rhythm, she is replete. She sleeps.”