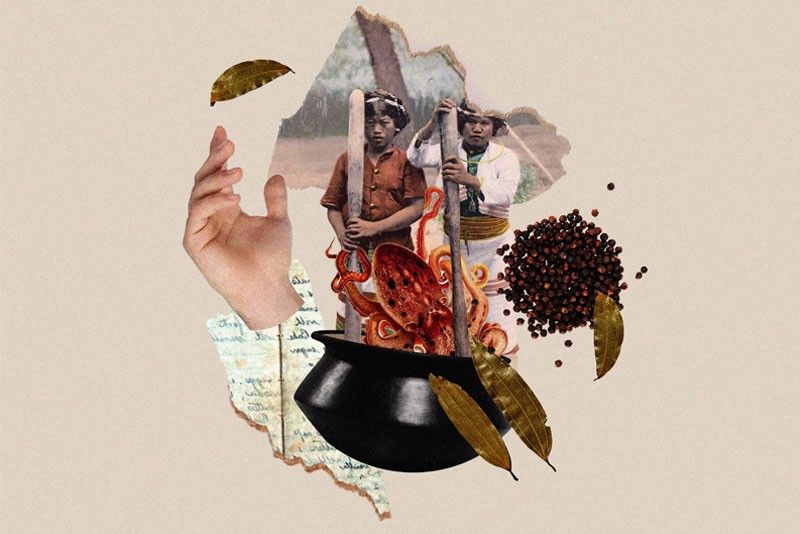

The Adobo Effect

Any seasoned seafarer without access to ice will always sail with a substantial portion of adobo on board. Anything can be made into adobo.

MANILA, Philippines — It’s getting away,” the boatman shouts. On a remote island in Palawan, Philippines, I spend a good part of the morning trying to catch a live octopus for lunch. In shallow aquamarine waters, between the corals, a medium-sized octopus fights back. Its tentacles slap against my arm and squeeze my wrist tightly. The boatman holds a long bamboo pole and continues to poke and prod. We had been snorkeling along the reefs before it caught his eye. Towards noon we manage to get it out from the rocks.

To put it out of its misery, the boatman pushes the head of the octopus, turning it inside out. We hold our kill — barbaric as it may sound — triumphantly above our heads. I had great plans of poaching it in white wine and visions of charred tentacles brushed with a puree of ginger, garlic, fish sauce, lemon, herbs and chilli. We have supplies on deck, but the boatman who suffered the most during the hunt proclaims with a wide grin, “This will make the best adobo.” I return to the boat, dejected.

Any seasoned seafarer without access to ice will always sail with a substantial portion of adobo on board. The vinegar in the dish makes it keep well. In the week that we had traveled together along the islands, we had pork, chicken and squid adobo teeming with the standard grilled fish. He made sure I tasted every variation possible. “Lahat pwede i-adobo,” he says proudly. Anything can be adobo’d.

Before Spanish colonization in the late 16th century, Filipinos cooked pork and poultry in salt and vinegar as a mode of preservation. Pedro de San Beunaventura, a Spanish missionary, recorded the cooking process and noted it as adobo de los naturales or the marinade of the natives. The local palate still leans toward sour, cooking with a variety of vinegars from each region — from rice and sugar cane, to palm and coconut vinegar.

Adobo is the unofficial national dish of the Philippines. It is savory, salty, sour and aromatic. It originated from the Spanish word adobar meaning to marinade. This process of cooking is popular in the archipelago. Adobo can involve a protein, seafood or vegetables. Traditionally it is made with a mixture of pork and chicken. The marinade consists of chopped garlic, peppercorns, bay leaf, vinegar and soy sauce. In a palayok or clay pot the meat is browned to a crisp in oil, then stewed or braised in its own marinade. Soy sauce was brought into the country by Chinese traders and became an alternative to salt and fish sauce in a number of local cuisines. The adobo that we now know is a lot darker than its original form. It is also a difficult dish to make on the first try.

This hearty and comforting stew does not have a universal recipe among the over 7,000 islands in the Philippines. Some call for chilies and coconut cream in the southern Luzon island of Bicol, turmeric in Cavite, brown sugar, annatto and even ground chicken liver and gizzard in other regions. Adding a new component will certainly disgruntle a few Filipino grandmothers. Each household has its own cooking process — from sautéing, braising to frying. The wizardry of its sour, salty, rich and pungent flavors is a common point of contention among friends and family across dinner tables. But whichever version one ends up with will be a source of comfort and a fond reminder of home.

Ingredients

Marinade

2-3 bay leaves

1 tsp whole peppercorns

1 head garlic, crushed or finely chopped

3-4 birds eye chilies chopped

1 tsp muscovado (unrefined) sugar

1/2 cup soy sauce

1 1/2 cup red cane vinegar

1 cup coconut milk

1 kg chicken thighs or (your choice of cut)

Salt to taste

2 tbsp oil (for frying)

Garnish

1 tsp chopped coriander

1 tsp chopped scallions

Preparation

1. In a large glass bowl combine all ingredients for the marinade. Add chicken. Cover and leave to soak for a minimum of 2-3 hours or overnight in the refrigerator.

2. Pour the chicken mixture into a Dutch oven or a large lidded pot. On high heat, bring to a boil. Lower heat, simmer for half hour or until chicken is tender and the sauce has caramelized. Add water if necessary. Occasionally turn chicken during this stage of cooking.

3. Remove chicken and set sauce aside.

4. In a separate non-stick pan, heat oil. Fry chicken in batches over a medium heat, until brown and crisp.

5. Strain sauce to remove peppercorns, chilies and bay leaves. Add sauce to the chicken. Simmer until the liquid has reduced to a shiny glaze. Top with chopped coriander and scallions. Serve hot on a bed of rice paired with a local atchara (pickled papaya).

Adapted from “Memories of Philippine Kitchens by Amy Besa and Romy Dorotan” (2006).