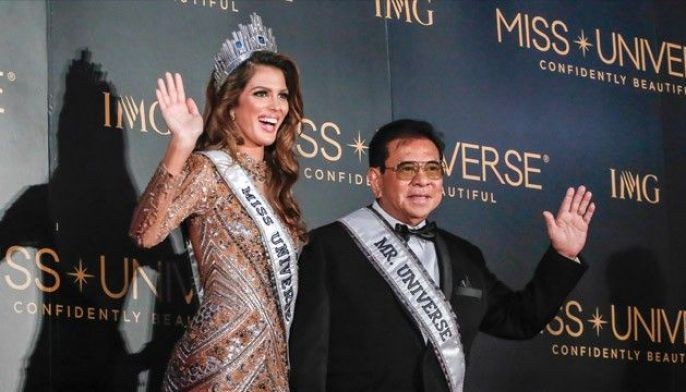

Inspiring truth in the age of fake news

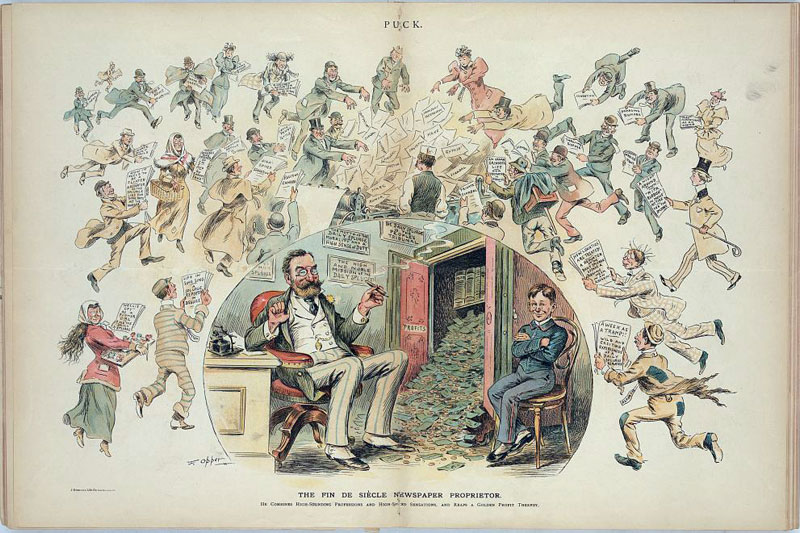

Reporters with various forms of “fake news” from an 1894 illustration by Frederick Burr Opper. Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons

MANILA, Philippines - Evelin Nicole da Silva Sousa was a typical nine-year-old girl who loved to watch TV and football. She lived in her maternal grandfather’s house in the rural town of Altamira in Para State, Brazil. But her joyful youth was forever taken from her when her grandfather raped and killed her one night in 2014.

News of Evelin’s death shocked the sleepy town of Altamira, though it didn’t make headlines throughout Brazil. Her rape and murder caused anguish in an unlikely country more than 18,000 kilometers away — the Philippines.

That’s because a photo of her dead body was posted on Facebook on Aug. 27, 2016 by a former campaign spokesperson of President Rodrigo Duterte and made it appear that she was a Filipino victim of drug-related violence in the country.

It was through Laviña’s post that the poor Brazilian girl became fodder for fake news. Laviña’s post was shared by more than 4,900 followers while more than 4,700 people reacted to it. Fake news websites such as Trend Titan, Public Trending and News Info Learn as well as social media accounts of known supporters of President Duterte also shared his post. When former Interior Secretary Rafael Alunan III shared Trend Titan’s story regarding Laviña’s post, it got shared more than 1,600 times and reacted on by more than 2,300 people.

Responses to Laviña’s post reveal netizens’ initial belief that the photo was of a Filipina victim, with many echoing Laviña’s tirade against the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) and critics of President Duterte’s war on illegal drugs. CHR’s social media accounts received a barrage of attacks from irate netizens in the weeks and months after Laviña’s post went viral, forcing the commission to issue a clarification of what its mandate really is.

It was only two days later after journalists Froilan Gallardo and Inday Espina-Varona shared the link to a story by Brazilian website Na Boca do Povo, where the original photo was posted, that truth was finally revealed and Laviña’s post was exposed as fake news. While several credible news agencies ran the exposé, Lavina’s post continued to garner likes and was continuously shared by other fake news websites.

Laviña’s post is one example of how some supporters of President Duterte have engaged in the production and dissemination of fake news. But this doesn’t mean that fake news, as a phenomenon, happens in one color in the political spectrum alone. It has happened (and can happen) in other colors in the spectrum as well.

Take the case of the fake news posted on Facebook by Silent No More, an organization critical of the abusive and corrupt policies of the Duterte Administration. On June 2, 2017, several hours after a lone gunman attacked and set fire to Resort World Manila, a resort and casino in Pasay City, Silent No More posted on Facebook a photo, which they said was sent to them by a casino employee. They said the photo, a screengrab from CCTV footage, shows there were two gunmen allegedly involved in the attack and asks if there was possibly a government cover up of the incident. They also used the hashtag #TanimTerrorista in disseminating the post.

Just minutes after Silent No More posted the photo, the group deleted it after several netizens found out that the photo was from a different attack—a casino robbery at the Savannah Hotel and Casino in Paramaribo, Suriname on Dec. 28, 2011. The photo was screengrabbed from the casino’s CCTV footage of the attack, which was uploaded in YouTube in 2012.

While Silent No More already deleted the post and issued an erratum on its Facebook page, the incident already help tarnish the group’s reputation among supporters of President Duterte, who see the group as bent on tarnishing the government’s image.

What is fake news?

Laviña’s post is just one example of how potent fake news is in shaping public opinion. Such stories have the power to polarize different sectors of society and can even lead to breakdown in law and order once readers commit violent actions in reaction to the story.

But what stories can be classified as fake news? And how can it be distinguished from news stories that we get from established news organizations?

The Philippine STAR spoke to Danilo Arao, veteran journalist for news websites Bulatlat and Pinoy Weekly and associate professor of Journalism at the University of the Philippines Diliman, to learn what exactly is fake news. He cited the article Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election, which came out in the Journal of Economic Perspectives for its definition.

“Academics Hunt Allcott and Matthew Gentzkow define fake news as ‘news articles that are intentionally and verifiably false, and could mislead readers.’ Taking into account the normative standards of journalism, we may also stress that fake news is synonymous with disinformation and outright lies being peddled through the mass media by certain individuals and interest groups that can gain from the resulting social division, confusion or even chaos,” Arao said.

Many of the fake news stories circulating the internet today, including Laviña’s post, can be categorized as fake news given this definition, as these stories are outright lies designed to incite anger, fear, and in some cases, violence.

What is fake and not?

Fake news, however, should be distinguished from erroneous news, that is, news that turned out to be incorrect because of a journalist’s or media organization’s oversight in terms of the veracity or quality of the report. And it’s a common occurrence in the media industry that is often misconstrued as deliberate even when it’s not.

“Errors in media reportage are a bit tricky because these could be misleading and journalists could be unwittingly used by their unscrupulous sources. In other words, there are honest mistakes that should not be classified as fake news but it is probable for journalists to be victims of kuryente which would result in misleading or deceiving the audience,” says Arao.

Moreover, fake news should also be distinguished from satire, which is a form of literature that employs humor, irony, exaggeration, or ridicule to make commentaries on current political events or personalities. Satirical websites like So, What’s News or Professional Heckler are often misinterpreted as fake news websites even though their authors have clearly indicated the satirical and fictional nature of their stories.

“Analyzing the history of the press in our country, satire is very much part of Philippine journalism, as in the case of Graciano Lopez Jaena’s Fray Botod. If professionally done, satire cannot be considered as fake news as it helps in shaping public opinion by making audiences think, mainly through an exaggerated depiction of reality,” Arao explains.

Not old news

One might think that fake news is a phenomenon unique to our generation, but it’s not. Fake news goes back to as far as the early days of printing. After Johannes Gutenberg opened the first printing press in Europe in 1439, news pamphlets began to grow in popularity throughout the continent, usually posted on the bases of statues or distributed to townsfolk in town squares. Most of these news pamphlets, however, lack authentic and legitimate sources or references.

During the 1521-22 Papal Conclave to replace the deceased Leo X, Italian author Pietro Aretino published several pamphlets maligning candidates for the papacy and posted it in pasquinades or “talking statues” at Rome’s Piazza Navona to sway public opinion in favor of his candidate Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, who lost to Adrian VI.

Similarly, the so-called French canards published rumors and disparaging stories about Queen Marie Antoinette during the French Revolution which ultimately led to her death in the guillotine in 1793.

One of the first instances of fake news appearing in mainstream media was the Great Moon Hoax of 1835, which was published by New York-based newspaper The Sun. The hoax, perpetrated by reporter Richard Adams Locke, tells of the supposed discovery of life on the moon by real astronomer Sir John Herschel, who made no such discovery.

Why is fake news popular?

Fake news has been around for centuries, and yet, despite readily available information today which can disprove these stories, a lot of people remain convinced by it. There are certainly factors involved in its continuous spread and potency in social media and the internet.

“I think news consumers gravitate to social media because of accessibility and speed of getting breaking news, and not necessarily because of distrust of mainstream media. Fake news websites, because of their nature, can be initially attractive because they offer stories that do not appear in mainstream media,” says Ana Marie Pamintuan, STAR editor-in-chief.

Indeed, it’s the attractive, eye-catching nature of fake news stories that basically drives audiences to fake news websites. Their headlines are often suggestive of intrigue, conspiracy or mystery, effectively exploiting audience curiosity — pejoratively called clickbait in journalism parlance.

Moreover, several fake news websites are known to directly engage with audience by crowdsourcing stories from them or interacting with them in forums or social media pages, giving audiences a semblance of being part of news making — something you rarely see in traditional media, where communication between audience and journalists are typically polite and formal.

“Audiences are given a false sense of empowerment and entitlement interacting with fake news websites/social media pages as they are more able to interact with the authors and other social media users. The occasional use of foul language in such sites/pages (whether in the actual article or comments section) also gives some audiences a warped interpretation of freedom of expression which they can “maximize” without any fear of being called out for being ungrammatical and fallacious,” Arao explains.

But the potency of fake news websites doesn’t just lie on how their content is presented. Perhaps the most crucial factor in the proliferation and potency of fake news lies in the human brain.

According to psychoanalyst David Brauscher, our biases also play a key role in why we are gullible to fake news. He identified two types of biases as critical in such phenomena: implicit bias and confirmation bias.

Implicit bias refers to the idea that as humans, we tend to group people into categories, while confirmation bias refers to our tendency to seek out information that confirms what we already know or believe to be true.

“When implicit biases and confirmation biases work together, their potential to lead us astray increases exponentially. As our implicit bias leads us to trust and view more positively those of our own group, we become more insulated, only hearing from people of our own group. As those of our own group share our beliefs, they share ‘facts’ that confirm our beliefs. It is a feedback loop, and we end up living in a bubble,” Brauscher wrote in a piece for Psychology Today in December 2016.

Fact-checking lies

Clearly, given our own brains make us gullible to fake news, it is highly important that we should combat its spread in cyberspace and other forms of media. In the age of fake news, there must stand a group of individuals that would inspire truth in journalism and debunk the outrageous claims and fictitious stories that fake news websites peddle. And already, there are several news organizations that are at the forefront of combatting the spread of fake news in the Philippines.

Among them is Vera Files, a non-stock, non-profit independent media organization founded by several veteran Filipino journalists in March 2008. Since its inception, it has engaged in research-intensive, in-depth reports regarding various current events in the Philippines, which they publish in different formats.

More recently, with the rise of fake news prior to, during and after the 2016 Presidential Elections, Vera Files embarked on an initiative to fact-check various public statements made by key personalities on either side of the political spectrum in the country. Sometimes, they also monitor key personalities who have flip-flopped on their positions on certain issues.

“We track false public statements that could have an impact on the public and we counter that with evidence. It’s a rigorous process that involves three editors, two writers and a researcher. We also accept news stories or fact-checks from credible contributors,” says Vera Files president Ellen Tordesillas in an interview with STAR.

On its official website, verafiles.org, one can clearly read through the methodical approach that Vera Files employs in fact-checking public statements.

For example, in its fact-check of President Rodrigo Duterte’s statement last year that “Iloilo is the most ‘shabulized ‘place in the country,” Vera Files posted the transcript of Duterte’s exact statements to prove that he said what was said. They then debunked his statements using data from the government’s very own Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA).

According to PDEA, of 81 provinces and 27 cities in their list in terms of number of drug-affected barangays from January to August 2016, Iloilo province ranked only 79th while Iloilo City ranked 51st. The list was dominated by cities from the National Capital Region.

Aside from Duterte, among other notable personalities that Vera Files has fact-checked include US President Donald Trump, Sen. Cynthia Villar, Presidential Spokesperson Ernesto Abella and Justice Secretary Vitaliano Aguirre. Their fact-checks have also been published by mainstream newspapers such as Abante and STAR.

“What is our purpose here? In the same way that truth empowers people to make good decisions, anything that is a lie can confuse people and lead them to bad decisions. Which is why it’s important that you expose a lie and reveal the truth,” Tordesillas explained.

Vera Files’ fact-checking has earned them a modest following in social media, with 21,500 likes on Facebook and 2,825 followers on Twitter. While that’s smaller compared to the following of some fake news websites, Tordesillas says they are not worried about their popularity.

“Just because you’re not popular doesn’t mean you’re wrong and doesn’t mean you should stop doing it. You do things because you believe in it. Who else is going to do it if you’re not going to do it?” she says.

Using tech to fight fake news

Combatting fake news takes more than just exposing the lies and countering them with facts. To stop the spread of fake news, its online presence must end. Which is why some tech-savvy journalists decided to develop an online application that allows internet users to flag content they think is fake news.

Fakeblok, the online application, is a Google Chrome web browser extension developed by the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) and advertising agency BBDO Guerrero.

“It’s a Google Chrome web browser extension that you have to download, and once downloaded, it will tag a news website as fake based on the list of fake news websites that we already have. It is our way of helping the people to identify a fake news website and prevent people from spreading it,” says Elizabeth Panelo, Secretary General of NUJP.

According to Panelo, since the Chrome extension was launched last month, it has been downloaded by almost 2,000 users of the web browser. Their team has also moderated and flagged more than 2,000 fake news stories and prevented more than 1.6 million people from reading them.

It’s been less than two months since the Chrome extensions was launched, and though it looks like a promising solution in fighting fake news, Panelo admits they still haven’t flagged some fake news websites.

“We won’t be able to flag all of them. We still have an extensive list to thoroughly study and verify to avoid flagging legitimate news organizations. Besides, even if we flag them, it’s just easy for people who earn a living making fake news websites to make another one,” Panelo states.

She adds more than regulating the presence of fake news on the internet, media must be also be a self-regulating industry to further prevent the spread of fake news. “This is a public trust that we’re doing. And if you are doing your job the right way, if you’re giving truthful information to the public so that they can make an informed decision, then that is already your service to them,” Panelo says.

And she’s right. Perhaps the fight against fake news is also won by people who adhere to stringent standards of truth and accuracy within the profession of journalism.

This is exactly what STAR has been doing for the past 31 years as the country’s leading broadsheet newspaper. Even as fake news proliferated in other tabloids and newspapers, and now, on the internet, the company has remained committed to what it does best — letting the truth prevail. And that has inspired many Filipinos to make good decisions that have positively changed the lives of their fellow beings and helped the country become a better democracy.

It wasn’t an easy commitment to keep; there have been challenges along the way, especially now that print media is competing with other platforms, including fake news websites, for survival, but the newspaper has carried on.

“In covering and presenting the news, we adhere to journalistic ethics that social media cannot guarantee: accuracy, fairness and objectivity, accountability to our readers. We can be sued, fined and sent to prison for violating those ethics. Readers can stop buying the paper. The pressure for accuracy and fairness is greater for a newspaper because mistakes are preserved forever in black and white. A newspaper’s biggest asset is credibility as a news provider. Credible, responsible journalism is our ticket to long-term survival,” says Pamintuan.

She adds: “Journalism will not be killed by social media and the digital age. We continue what we are doing, vetting each story for solid journalism. The best way to fight fake news is to present the real story. At the same time, we keep investing in new publishing technology to package the news in an interesting way. People can compare our product with the unaccountable, unverified stuff they get on social media. [But] there is no substitute for genuine journalism. As our newspaper declares, the truth shall prevail.”

In the era of fake news and fake news websites, lies will continue to be peddled and believed, but rest assured the journalists and media organizations like The Philippine STAR will continue shining the light on the truth.