10 lessons from the grand old man Washington SyCip

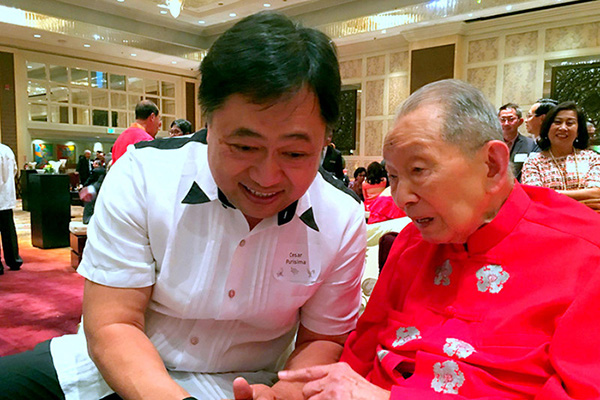

Former Finance Secretary Cesar Purisima writes about the valuable lessons from his late mentor, Washington Sycip.

Mr. Washington SyCip was to me, first and foremost, a mentor — a fact I feel incredibly fortunate and grateful for. As the nation mourns the passing of one of the tallest, most enduring pillars of its business community, I write to honor his memory in my own little way, by recounting just some of the lessons the grand old man has taught me and many others.

I would like to think this is a good way he'd like his life to remembered by those he'd left behind anyway—not adulating accounts of how great he was, for he always eschewed those things, always referring to himself as a mere bookkeeper—but a commitment to keeping his little nuggets of wisdom in mind and the values he'd imparted in our hearts.

1. Learning

WS read widely and voraciously, and he expected you to do the same. I dreaded flying with him before because there was no peace in the cabin. He'd hand me a copy of an article he found interesting—The Economist usually, and often with notes and underlines—and ask me what my thoughts were. Having WS around kept me on my toes; I had to be sharp and ready to think. Rather, my mind always had to be thinking.

I guess this is why WS was such a tough but rewarding boss. There was a challenge to constantly learn. He expected people to constantly retool and upskill themselves, and where he can, he'd help. He emphasized the importance of continuing education and walked his talk by devoting a huge part of his life to the Asian Institute of Management and Synergeia.

There is a certain humility to keeping your mind young, in knowing that you can never know enough. That humility is what keeps us from being obsolete. Continuous, life-long learning, WS often says, "breeds excellence."

2. Hard work

WS was inarguably the principle of hard work personified. Punctuality was a sacred virtue. He'd be at the office at 7 a.m, and if you weren't inspired to do the same you'd be ashamed you weren't. Work on Saturdays could not be lifted for so long as the client is likewise on the clock. In the auditing profession where leaving no stone unturned is our bread and butter, he preached and lived thoroughness.

WS also showed us how hard work is reflected in the little things. He had great attention to detail. He'd remind us how little instances of wastefulness in the office could add up to millions, eventually. Each business card was marked with notes—who, when, where, and how he had met the person, for example. He made sure our offices—and even toilets—were clean, as this signified to our clients and to ourselves how seriously we took our work.

If you cared enough about your work, your actions would show it. One of the first encounters I had with WS when I was a young staff back then was in the elevator, where he spotted me carrying working papers without a bag. "Young man," he said, "who is your partner-in-charge?" I proudly gave him my superior's name, not knowing he was going to dress my boss down for letting me carrying working papers without a briefcase. I guess hard work also means taking great care to attend to even the minutest details of the job.

3. Creating and delivering value

I guess this impetus to bring value has a deeper rationale for WS. He wanted us to make a difference in whatever we were doing, to make sure that there is unique value added with our work. In a way, he demanded us to have a strong sense of purpose. For after all, what are we doing in the conference room if what we're saying is just a regurgitation of what the guy beside you said?

4. Interacting with people

When you're a young staff member attending cocktails or dinner, it's easy to feel shy, as though there is no reason for important clients to be talking to us. So we just clumped together and talked to each other, bubbled up in the pockets of our little comfort zones. WS thought that was stupid. He forbade us from talking with just fellow SGV employees, and encouraged us to mingle and talk to clients.

In a way, this reflects his entire philosophy about people. He believed in the power of networking, in developing and cultivating a web of diverse individuals one could either learn from or to synergize and work with. He always spoke highly of how much he learned from his many friends, the likes of which are Ambassador Ramon Del Rosario Sr., Jose Fernandez, Roberto Villanueva Sr., Dr. Stephen Zuellig, Alex Melchor, Col. Joseph McMicking, Maurice "Hank" Greenberg, and yes, even Henry Kissinger and David Rockefeller. To this day, I can't think of any other person with a more extensive and powerful network as WS.

He was a master in the lost art of listening. Where we sometimes preoccupy ourselves thinking of what to say during conversations and trying to get a word in edgewise, WS would patiently listen. After every trip he would give us a very detailed account of who he met and more importantly, what he learned from each encounter.

He'd teach younger SGV staff too how to conduct ourselves, by inviting those he thought who had potential to private dinners, quietly observing unbeknownst to them, and giving feedback on how to do better.

One other elegant piece of advice he once doled out, "Be like a moth. Close enough, but not too close to get burned."

5. Investing in people, process, technology

He also invested in people by posting them abroad for deep immersion. In my case, I was fortunate to have been assigned to Washington DC and the Middle East. Living in Saudi Arabia for more than a year thrust me into a completely different world and forced me to learn and adapt in unfamiliar environments. WS thought this to be a two-pronged strategy: while enriching talents in foreign assignments, he was simultaneously able to develop the profession in the region, especially in countries where the profession was still in its nascency.

WS would often give unsolicited but always appreciated advice, combining institutional relations with the employee with a more personal touch. Another one of my early encounters with him, also in the lift, started with him noticing the tie I wore. "Nice tie," he said, "let me show you how to do it better."

I am sure SGV alumni all have their own little anecdotes to tell, all pointing to the uniquely personal nature of his approach to people. Not once did he ever raise his voice on us in anger—and perhaps therein, counterintuitively, lies the secret to the air of authority and respect he carried wherever he went.

He encouraged SGV to embrace the future, investing in technology and being ahead of the curve. From his experience as a code breaker during World War II, he saw the power of communications technology in making the world a much smaller place. As technological development grew exponentially, he saw the digital age as an opportunity to leapfrog national development and sought to learn as much as he could from it. In fact, WS was actually one of the pioneers of the Philippine BPO industry having started the Manila Solutions Center of the then-Andersen Consulting (now Accenture) in the 1980s.

He would also emphasize the importance of process. Perhaps in our profession ignoring process is one mistake too costly to make. He thus preached the gospel of "built-in quality, rather than checked-in quality," the logic being that if the process has mechanisms and levers to ensure quality, then you wouldn't have to waste time and money on a secondary layer to check and revise.

6. Leadership and stewardship

WS also made clear how synonymous leadership was to stewardship, how leading the firm is about taking care of it for the next generation. All managing partners run but a relay race, and we must do well to remember that while we hold the torch we must run as fast as we can and hand the torch to our successor burning brighter than when we first held it. And such a successor, he counseled, should have already been on our minds the very first day of taking over as head of the firm.

Leadership, like learning, is also about humility. WS believed in MBWA (management by walking around). He was very light-footed, and would often surprise partners and associates alike by suddenly appearing in your workstation to check up on you. He encouraged us to get to know younger staff members (as he very well did with us) through formal programs and informal conversations. I am so glad I took this piece of advice to heart—that's how I met my beautiful wife in the first place.

7. Integrity, prudence and responsibility

If you're part of the SGV family, you would know WS had the utmost priority for prudence and acting appropriately. From institutional mechanisms like Chinese walls to maintain professional responsibility in case SGV is engaged in both the buy-side and the sell-side of a deal, to simple rules like not having flashy, expensive cars, WS showed us that the good and virtuous life is one of measured moderation.

WS always preached that there is one overarching value in the accounting profession, and that is of integrity. No matter which market we operate in, professional credibility is our common currency. Reputation takes lifetimes to build but only a mere second to destroy, he would always remind us, so our actions, decisions and relationships must always put a premium on integrity.

8. Service

Country first—even above the firm. WS devoted his life to advancing the development of the nation any way he could—from serving as both the institutional and personal advisor to entrepreneurs to philanthropic pursuits in education. He was always a firm believer that the key to our nation's development problems starts with investing in education.

9. Generosity

WS espoused the principle of giving back, and he expected no less from all of the partners at SGV. He required us to donate to the Asian Institute of Management or other NGOs and charitable institutions, and very soon the art of charity and gift of generosity was instilled in our hearts.

In just two decades of existence, WS established the SGV Foundation to institutionalize social responsibility. After his retirement, he also helped organize the Philippine Business for Social Progress and focused on microfinance, entrepreneurship and public health. These three priorities, along with his first love (education), are what the Philippines sorely needs for social advancement.

10. Meritocracy

WS discouraged his children from joining SGV. If they succeed, people would have said it was because of nepotism. If they do not do as well as he did, then people would have considered them as failures.

In the same vein, there was simply no room for favoritism at SGV. SGV was run as a true meritocracy, where everyone had equal opportunity to have their hard work and talent rewarded.

———

The Philippines is filled with Goliaths and Davids trying to beat or be Goliaths themselves. But how many of us remember Nathan from the Bible as well as these two characters? Nathan the wise prophet, the valued advisor in King David's court?

Washington SyCip could very well be a Goliath or a King David himself, and in many respects he was indeed a towering titan in the Philippine economic landscape. But he lived his life as a Nathan, a sage advisor and enabler to many of the nation's successful tycoons, entrepreneurs, and leaders—the simple bookkeeper whose wisdom ran in the veins of the nation's economy for almost three-quarters of a century.

In honor of Washington SyCip's memory, we remember his lessons and strive to live his wisdom out.

Cesar V. Purisima served as finance secretary of the Philippines from June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 under President Benigno Aquino III, and from February 15, 2005 to July 15, 2005 under President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. He was also a former chairman and managing partner of SGV & Co.

- Latest

- Trending