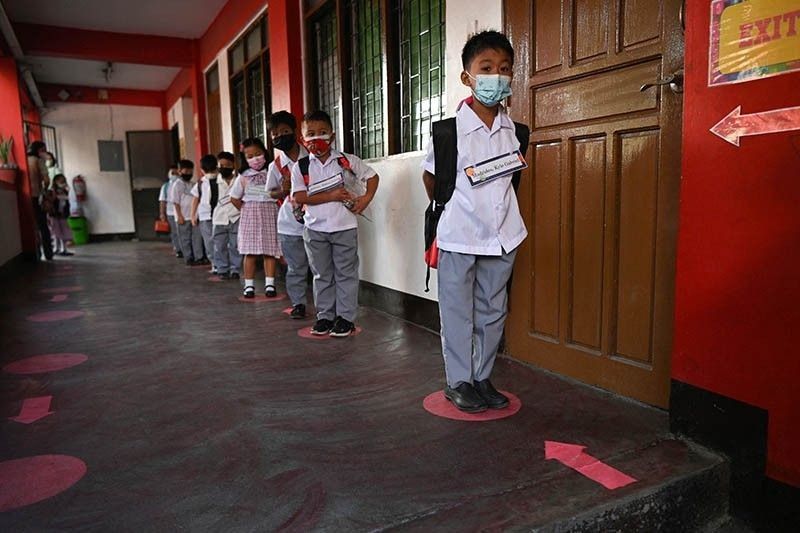

Landmark law for children with disabilities still unimplemented a year since passage

MANILA, Philippines — Any parent of a child with a developmental delay often just wishes for one thing to happen to their child in the span of a single school year: for them to be understood.

This is what Alex*, 42, a mother to a five-year-old child with a speech delay, had hoped for when she enrolled her son in a private school to help ease him into the shift from modular to face-to-face classes.

"We saved up the money to enroll him in a private school. Class sizes there are smaller compared to public schools," Alex told Philstar.com in Filipino during a phone interview. "We even hoped that he would make friends."

But she and her husband made the tough decision to pull their son out of school weeks after classes began after they saw photos and videos sent by their teacher to their class group chat. In these, they saw their son sitting in a corner facing the window as his classmates played. He walked around the back of the class while other children answered a test.

Her son would cry every time she dropped him off in class.

“I anticipated that he would have a hard time because it’s his first time in a regular school, but it still hurt to see him excluded,” Alex said.

Law passed in March 2022

Advocates of inclusive education and persons with disabilities lauded the passage in 2022 of a landmark law that would pave the way for improved programs and services for learners with disabilities.

Republic Act 11650, or the Inclusive Education Act, was signed into law in March 2022. It mandated all cities or municipalities to establish an Inclusive Learning Resource Center (ILRC) – a physical or virtual one-stop-shop providing teaching and learning support to students with disabilities while providing free therapy services.

While the passage of the law was hailed as a beacon of hope for children with disabilities, a year later, the government has yet to release its implementing rules and regulations (IRR), which would have moved the needle closer to ensuring students with disabilities had access to quality education and health services.

Alex, who resides in Cavite, would have been among the first in line to avail of an ILRC’s services and enroll her son in speech therapy, she said. "But I never even heard of that law until now," she admitted.

Regular classrooms can’t cater to all students with disabilities

Alex posted her concerns about her son on a Facebook group for other parents with children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

"I should just find a regular school who could ‘handle’ my child. That was the most common advice," Alex said. Her son has yet to go back to school due to Alex' mounting financial problems.

Cristina Aligada-Halal, who has taught in SPED for 16 years and has led Miriam College’s Special Needs and Inclusive Education program since 2018, said that parents of students with disabilities are often backed into a corner of choosing a school without enough learning resources to cater to their needs.

Sometimes, Aligada-Halal said, it is the school itself that sends parents a blanket disclaimer that it is not "trained" to teach students with special needs. This leaves it up to the parent’s discretion whether to take a risk. If it doesn’t work out, that would be on them.

"There are still a lot of schools that turn away students for the simple reason that they will say: ‘We are not trained. We don’t want to short-change the child,’" Aligada-Halal said in a phone interview with Philstar.com.

"What happens is that it now becomes mostly the parent’s accountability. It’s like, you enrolled your child there knowing that it is not an inclusive institution. It becomes mostly their choice and burden to bear," she said.

However, parents like Alex, who cannot pay for a private tutor, cannot afford to be picky. She believes her son would also be bullied in larger public schools despite the free tuition.

"In public schools, the usual problem is that they do not turn down students. But not all schools have trained teachers in inclusion, and not all has a SPED center or SPED program," Aligada-Halal said. "So we are really after something that can be put into law. At least in writing, there is a legal basis to make them inclusive."

RA 11650 mandates the government to take a "whole-of-community" approach involving the Department of Education, the Department of Social Welfare and Development and the Department of Health to address the growing number of learners with disabilities in the country.

It would take at least five years for all public and private schools and ILRCs to fully comply with the law in making inclusive education accessible for learners with disabilities, according to its provisions.

With the delay in the release of its IRR – beyond the 90-day period given for the crafting of the IRR of newly passed laws – its full impact has yet to benefit parents like Alex whose children struggle to adjust to a regular classroom.

Worse, the law misses out on addressing the needs of the estimated 60% of children with disabilities not enrolled in any school or learning center, according to the Department of Social Welfare and Development Listahanan’s 2019 data.

Enrollment among learners with disabilities were freefalling during the pandemic, with DepEd recording only around 126,000 learners with disabilities enrolled in DepEd schools in 2021. This is 65% lower than the 360,000 students enrolled in 2019.

Toothless law

E-Net Philippines, a civil society network of education groups, called on the government on March 22 to lay down clear guidelines on how to implement the law, which is meant to address the education and health needs of around 5 million Filipino children with disabilities.

"The development and implementation of IRR is a critical step in translating the law into action and achieving its intended outcomes. The IRR provides clear guidelines and procedures that help ensure that the law is implemented consistently cross different settings," the group said in a statement.

Zhanina Custodio, a professor at the Philippine Normal University who formed part of the PNU team that DepEd consulted in crafting the IRR, said that the lack of an IRR makes it difficult to know whether schools outside of urban centers will comply with its provisions, specifically in finding and identifying students with special needs.

"There is also the penalty. If there is no IRR, who are we going to penalize once there is a student or person who is discriminated in entering regular classrooms?" Custodio told Philstar.com in a phone interview.

Custodio added that academics and advocacy groups have long sought the passage of the Inclusive Education Act since 2018. Custodio participated in Senate hearings about the law and explained the then-unfamiliar concept of inclusivity in education.

"I even cried when it was signed. It was really difficult to explain what inclusive education is. Imagine you had to defend what inclusion is among policymakers, among stakeholders, including parents and even teachers," she said.

"It took too much time. It’s because the pandemic also happened."

While Custodio said that they had already presented a proposed IRR to DepEd in December, it is unclear when the agency would decide on a final version of the IRR — or if it already has.

Philstar.com reached out to DepEd spokesperson Michael Poa for comment. He has yet to respond as of this post.

"The principle of this law is a whole-of-community approach, and a lot of agencies and stakeholders needed to have a voice in its implementation. That is one of the challenges in crafting its IRR," Custodio said.

Custodio added that without the law, there would be no clear policy on how to use DepEd funds in identifying students with disabilities in every locality, which is among the law’s salient points.

DepEd's SPED program was initially given no budget in the National Expenditure Program submitted to Congress for 2023. Its budget was later restored to P532 million — enough to convert the existing SPED Centers in the country into ILRCs, which have more resources and facilities.

But now the delay of the IRR of the much-sought-after law is snuffing out what little momentum of support has been given to children with disabilities — a sector that rarely clinches institutional power through legislation.

Aligada-Halal, who is also a member of the ADHD Society of the Philippines, said that some parents of children with ADHD she has spoken to are now "skeptical" a year after the disability sector celebrated the passage of the law.

"The conversation on disability rights has changed. Last year, when it was newly signed into law, everyone was so hopeful. But then towards the latter part of the year, (we saw that) nothing changed," she said.

"Schools don’t feel compelled to act on it because they are also waiting for instructions," she added.

Alex said that for now, she is hoping that her son could learn from homeschooling, which she personally gives to him during what little time she spares from online selling.

She does not have formal training in teaching children with speech delay but said "this is better than nothing."

*Name has been changed upon request.

- Latest

- Trending