A look at the country’s patronage politics

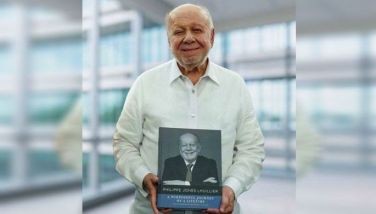

As everyone anticipates what has been described as a watershed election on May 9, one that is hoped to grant power to deserving selfless individuals who will genuinely work towards a more equitable society, a book that looks closely at patronage politics in the country is timely: “Patronage Democracy in the Philippines: Clans, Clients, and Competition in Local Elections” edited by Julio C. Teehankee and Cleo Anne A. Calimbahin (Bughaw, Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2022).

The chapters cover extensive research and field work on patronage politics, which began from 2012 to cover national elections in Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines with the support of the Australian Research Council with the Australian National University (ANU). For the Philippines, it covered the 2013 midterm elections and the 2016 national elections. More than 50 researchers from various universities in the Philippines were trained and hired to cover 45 locations in the country, some covering the entire province, others on specific congressional districts or cities.

As detailed in the Foreword by Paul D. Hutchcroft, professor of political and social change at ANU, the project researchers used “extensive political ethnography” as research method. They typically had close ties with the leaders they were researching on and had two to three weeks of work on the field, leading up to election day on May 9, 2016. The work involved interviews with local political actors, shadowing the candidates, attendance at and observation of campaign sorties, studying campaign appeals used, the networks through which patronage was distributed.

In his comprehensive Introduction, Julio C. Teehankee, book editor and professor of political science and international studies at the De La Salle University, distinguishes between patronage and corruption. Patronage has long been part of Philippine politics, built upon the “intricate networks of political clans, clientelistic ties and political machines” throughout our islands. Quoting previous studies, patronage democracy refers to democracies in which “parties and candidates primarily rely on contingent distribution of material benefits, or patronage, when mobilizing voters.” It is the benefit given by politicians to individual voters, campaign workers, contributors in exchange for political support. On the other hand, corruption happens when public benefits are exchanged for private monetary gains.

The tough question is explored with a review of literature: What accounts for the resilience of patronage politics in the Philippines?

Carl H. Landé is recognized for his pioneering work on rural patronage politics in the country in his “Leaders, Factions and Parties: The Structure of Philippine Politics.” The relationships between pairs of individuals called “dyadic ties”were common – which bound prosperous patrons dispensing goods and services to dependent clients for their support and loyalty.

The rise of the political machines is another factor, as these are specialized organizations set up to influence voter outcomes through benefits in terms of jobs, services, favors and money distributed to voters and supporters.

The political broker aka political operator has emerged on the scene with the change in patron-client ties because of the “gradual erosion of the social and economic status of traditional landowners in the Philippines.” The broker is tasked with the legitimate and illegitimate ‘special operations’ for campaigns.

The Philippine Assembly in 1907, the precursor of the Philippine Congress, is said to pave the way for local politicians to aspire for national power. Local political clans were then able to access the coveted pork barrel funds. “Pork-barreling was the first significant method of providing state patronage in the Philippines.” The pork barrel funds were seen as definite political advantage that could easily lead to reelection. The weakening of the patron-client ties then saw the role of the state as a new and chief source of patronage.

Interesting is the discussion on political dynasties, political clans that have managed to maintain power through generations. In a study of political dynasties in the country, these were observed: relatives occupying the same elective position over time or a relative succeeding to an elective position previously occupied by a relative or relatives occupying multiple elective positions simultaneously. In keeping with the Filipino concept of pamana, political offices began to be viewed as assets to be passed on to the next of kin.

There is also “warlordism,” referring to guns, gold and goons, referred to by various scholars as “caciquism,” “bossism,” and “sultanism.” While this may refer to local bosses in far-flung provinces, it is noted that there has been a downward trend of warlordism since the 1990s. There is also the rise of local politicians recognized for their managerial and technocratic approach like Jesse Robredo of Naga City, Edward Hagedorn of Puerto Princesa City, Rosalita Nunes of General Santos City, to name a few.

There is more substance in Teehankee’s Introduction than this column’s limited space can attempt to cover. He puts forward a review of literature that provides the proper context for the full appreciation of the chapters to follow.

This book is an ambitious undertaking that covers these areas of the country, ten case studies on Isabela, Manila, Makati, Caloocan, Camarines Sur, Cebu City, Cebu Province, Iloilo, Bacolod, Lanao del Norte. While these may not represent the profile of the entire country, it is a significant examination of patronage politics, how it has shifted and transformed. Yes, patronage politics is well entrenched in our political structure but the authors hope the study will point the way for academics, policymakers and civil society activists to be able to reflect and work together for meaningful democratic reforms.

* * *

Young Writers’ Hangouts are on April 9 with Mary Ann Ordinario and April 23 with Roel Cruz.

Write Things’ six-day summer workshop “Writefest” (now on its 8th year) on May 16, 18, 20, 23, 25, 27 is now open for registration. Open to 8-17 year olds, it will run from 3-4:30 pm every session.

Contact [email protected]. 0945.2273216

Email: [email protected]

- Latest

- Trending