Filipino fishers face exploitation by vessel owners and recruitment agencies

Part 2 of a two-part report. Read first part here.

MANILA, Philippines — “PAPA RINGING.” The words flash on Matilda’s* phone.

Inside their home built of hollow blocks, in between rice fields in a province just north of Manila, she calls her husband, Rene*, a fisherman turned carer in Ireland. They haven’t seen each other in five years

“My sons and I are used to not seeing him. Because of video calls at least we feel he’s here, even though he is not.”

Rene hasn’t been home for several years, due to the exploitative working conditions he faced in Ireland which left him undocumented. His working permission elapsed once he “ran away from the boat”.

It wasn’t his first time working abroad. Rene has traveled across the Pacific Ocean working in different roles on boats since the 1990s. His experience in Ireland was very different.

“I was sleeping in the boat the whole time, even [though] my contract said that my employer should be providing a flat. They didn’t even give us an allowance for food. We had to eat leftover meat and fish on the boat.

“Sometimes, we’d even ask other boats for food, and our rest time was only when there were storms.”

Philstar.com interviewed a number of migrant fishers in Rene’s position; who left vessels in Ireland due to working conditions they found exploitative. In some cases, the vessel owners were subsequently ordered to pay thousands in monies owed.

Yet this process can take years with many finding themselves undocumented during it, often resorting to fighting in the courts to make their status legal once more.

Modern slavery — which includes human trafficking and forced labor — is the illegal exploitation of people for personal or commercial gain. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) states that “a string of recent reports indicate that forced labor and human trafficking in the fisheries sector are a severe problem”.

This string of reports includes a number finding exploitation and trafficking within the Irish fishing sector by the MRCI in 2017, research from Maynooth University, and successive annual Trafficking in Persons (TIP) reports from the United States government.

Over the past six months, Philstar.com teamed up with journalists in Ireland to investigate modern slavery in the Irish fishing industry, with a focus on Filipino workers.

The team combed through almost 100 inspection reports and numerous other documents obtained through freedom of information (FOI) requests, submitted press requests to Irish government departments and agencies, and spoke to fishers, advocates, and those working in the fishing industry.

This investigation was supported by Journalismfund.eu’s Modern Slavery Unveiled grant program. A series of articles were also published by the investigative platform Noteworthy in Ireland and can be read here.

‘The worst’ in Ireland

NGOs and migrant advocates told our investigative team that migrant fishers are becoming undocumented due to the conditions attached to a specific visa — the Atypical Working Scheme for non-EEA crew in the Irish fishing fleet.

Bill Abom, deputy director of the Migrant Rights Centre Ireland (MRCI), said that employment permits are problematic but this scheme is “the worst version of the employment permit system” when it comes to people’s rights and the risk of exploitation.

This sentiment was echoed by every expert advocating for migrant fishers that spoke to our team across the NGO, trade union, academic and justice sectors.

At least 4% of non-EEA fishers in this controversial scheme have been formally recognized as victims of trafficking, with more fighting for unpaid wages through the Workplace Relations Commission (WRC) and Labour Court.

The WRC is an independent statutory body in Ireland that investigates pay and work conditions and awards compensation to workers in cases where breaches are found.

This Atypical Scheme was introduced following an investigation by The Guardian in 2015 which exposed how trafficked migrant workers were being abused in the Irish fishing industry. At the time, almost all non-Europeans working in the sector were undocumented, according to Michael O’Brien, fisheries campaign lead at the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF).

The scheme applies to specific fishing boats over 15 meters in length. This currently accounts for just over 170 vessels — 9% of the Irish fishing fleet, but may reduce to under 130 in the near future as many are poised to take part in the Brexit voluntary decommissioning scheme.

Of the 337 holders of valid Atypical Scheme permissions at the end of last year, the majority (48%) were from the Philippines. Fishers from Ghana, Indonesia and Egypt are also commonly employed on Irish vessels.

In 2016, the scheme was to provide a legal framework for vessel owners to regularize undocumented workers and provide “a legal path to recruit new people thereafter,” O’Brien explained.

Yet, experts state it has now become a vehicle to exploit the same workers it was introduced to protect.

Problems due to ‘specific policies and laws’

MRCI’s Abom said “there is no doubt from our side — whether they [the Irish government] will openly admit it or not — that clear mistakes were made in the design and implementation of the Atypical Working Scheme. And it created significant problems for fishers, many of whom became undocumented as a result.”

Five years ago — shortly after the commencement of the scheme — the MRCI published a report that was highly critical of the scheme following interviews with 30 migrant fishers. It found that over 80% were working more than 60 hours per week, with average hourly wages of just €2.82.

It is evident that little has changed in the subsequent years with similar findings reported in the Maynooth study last year — research funded by the ITF.

Lead researcher of this study Dr. Clíodhna Murphy, associate professor of law at Maynooth University, said: “Labor exploitation and poor working conditions are rife in the fishing industry”.

“Migrant workers are used and exploited within the fishing industry all over the world. This is a worldwide problem but the problems in Ireland can be traced to very specific policies and laws here.”

According to O’Brien the experience since the scheme’s introduction “has been a large element of non-compliance”.

For fishers “enrolled in the scheme and recruited in the subsequent years”, almost all that O’Brien has encountered were “not paid as per the requirement of their contract… or they are paid the absolute minimum”. This, he said, often results in “a significant underpayment” compared to hours worked.

Patrick Murphy, chief executive officer at Irish South and West Fish Producers Organisation (IS&WPO), which represents vessel owners, said that the government knew there was a problem with the Atypical Scheme for years and it was “causing chaos in the industry”.

“They [the government] have as much of a responsibility for anything going on with these fellas as anybody else because they knew it was a problem. The scheme was not fit for purpose and instead of fixing the scheme, they let it drag on.”

In regards to the alleged exploitation by vessel owners, he said: “In every single occupation, nobody’s perfect and there are other fellas mistreating fellas. We don’t stand by those people."

“If you treat these lads badly and they leave, you’re out of business. You can’t take your boat out without a full complement of crew.”

This scheme was set up to be different from the general working permit in Ireland which can be issued for two years and then renewed for three years. In contrast, the Atypical Scheme fisher permissions have to be renewed annually.

Crucially, after five years with a general working permit, overseas workers can apply for a ‘Stamp 4’ visa. These visas allow people to work or set up their own businesses without being tied to a specific employer. Holders can also apply for their families to join them in Ireland.

Fishers with Atypical Scheme permissions do not have this entitlement, though a number of cases are being brought to the Irish High Court in the coming weeks contesting this.

‘If you don’t like it, go the f*** home’

The fact that Atypical Scheme permissions tie fishers to one employer is one of its major underlying problems according to MRCI’s Abom. Though there is an option to move, all of those involved in this sector have highlighted the difficulties involved in moving, with around 15% of fishers doing this since the scheme’s inception.

“You can’t challenge an employer when you’re tied to them and you have no other choice,” he said, adding that he’d be a rich man if he had a euro for every time a worker came back to him and said: “We complained but they [the employer] said — ‘If you don’t like it, go the f*** home’”.

Workplace Relations Commission (WRC) findings back up Abom’s assertion about these employers — over 75% of vessel owners who employ non-EEA workers have been issued contravention notices since the scheme’s launch near the start of 2016. These included working without permission, issues with hours or work and rest and not providing wages due or leave entitlements.

Now, following pressure from the recent national and international reports, a review of the Atypical Scheme — completed in March but published last month — recommended that the scheme be replaced by a general working permit. It also calls for those currently availing of the scheme allowed to apply for a Stamp 4 permission after two years or shorter.

Both the ITF and MRCI told us that all current Atypical Scheme permission holders should have immediate access to a Stamp 4 visa. “We’re not talking about huge numbers here,” Abom said.

Following the review, the Irish Department of Justice announced on their immigration website that the permission system for fishers would “close for new online applications” at the end of the year to “provide for the transition” from the Atypical Scheme system “to the Employment Permit system”.

This news has been welcomed by migrant representatives and vessel owners alike though all advocates and representatives told our team that it is crucial that details of any changes are agreed with their involvement.

Problem solved? Not for Rene who has been left undocumented because of his treatment within the scheme. The cross-departmental review does not make any recommendations in relation to undocumented workers. And he is not alone.

‘We couldn’t buy food’

Matilda barely had enough money to feed her family because of what happened to Rene in Ireland. Source: Geela Garcia

Rene, who is in his 50s, worked long hours at sea, with little rest — sometimes at sea, sleeping for just one to two hours each night. Crucially for him and his family, he wasn’t paid for three months after he started his job.

“We had no salary. That is very hard. We didn’t even get any money to spend for us or to send back home. My wife was really angry about that.”

In the Philippines, Matilda answers the call. Rene tells his family he is doing fine “taking care of an older lady”.

He says he is trying to get permission to be allowed to work but his papers haven’t been settled yet. Until then, he has been shifting from different jobs including a painter, dishwasher, gardener, and construction worker, just to survive.

“There was a time we couldn’t buy food, we couldn’t buy rice because there was really nothing coming from him. We had a hard time eating three times a day,” Matilda said.

Both their sons, one in senior high school and one in his last year in college, had to stop studying for two years because of their situation. The eldest took a porter job which paid Php 250 per day.

“Sometimes he [Rene] would send us Php 1,700 to Php 3,000 a month just so we could survive,” Matilda recalled.

Their financial situation got so bad that at one point four moneylenders would come to their house “almost every day”. Matilda would tell them that she didn’t know when she would receive money from Rene.

His youngest son said: “I was so stressed because of what happened to my father, to the point that my hair was falling out. I had to accept that I will be delayed in my studies because there was no choice for me.”

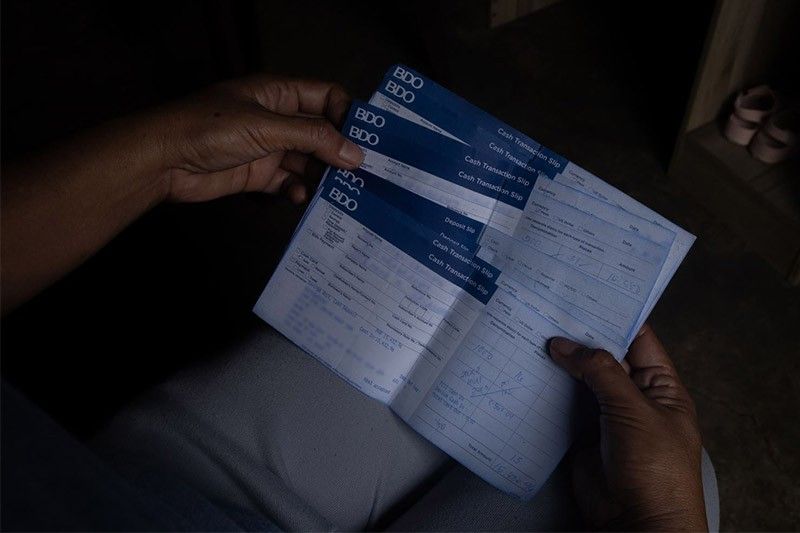

Matilda shows the investigative team cash deposits made to the lending company. Source: Geela Garcia

Inequity in the system

“My experience of undocumented [fishers] is of people who got sick with serious illnesses, ended up in hospital and were abandoned by their employers,” Sr Jo McCarthy who set up the Cork Migrant Centre said. She is highly critical of the Atypical Scheme, calling it a “form of indentured slavery”.

When we asked the Department of Justice in Ireland what it was doing to help fishers who became undocumented due to flaws in the Atypical Scheme scheme, a spokesperson said:

Undocumented workers remain outside of the recommendations of this report. However, it is open to any person who is undocumented in the State to apply to the Minister to regularise their residence.

It is unclear how many undocumented fishers that previously had Atypical Scheme fisher permissions are currently working on Irish vessels, but WRC inspection reports from 2021 and 2022 — obtained by the investigative team through FOI request — reveal that 40% of cases involved undocumented workers.

Just three of these 10 vessel owners were successfully prosecuted by the WRC for employing these undocumented fishers, with three unsuccessful prosecutions also reported. The prosecutions resulted in convictions for vessel owners and fines ranging from €1,000 (P59,000) to €3,000 (P176,000).

O’Brien from the ITF said that “the non-compliances with the WRC are not the full story”. He said that if a migrant worker raises issues, they risk not only losing their job but also their legal status “as he is left to try and find another vessel owner to hire him under the terms of the scheme”.

Working hours not logged

A large proportion of WRC cases we analyzed were in relation to the granting of annual leave and public holiday entitlements, as well as unpaid wages, unlawful deductions, and issues with payslips and statements of wages.

Nathan*, who came to Ireland from the Philippines last year, experienced many of these issues before leaving his employer’s vessel in the past few months due to conditions he felt he could no longer endure.

On board he had “almost no sleep” which impacted his eyes, he said while pointing to a red mark near his iris. Crew members from Eastern Europe — whom, he said, were paid more than €5,000 (P294,000) per trip — were also “intimidating Filipinos”, he claimed.

In terms of his pay, his salary was “not even minimum wage”, he said, and his working hours were not logged properly.

He had traveled to Ireland as his friends — who worked on different vessels — had a good experience on the Atypical Scheme, receiving bonuses. He thought this opportunity would enable him to finish building his house, which he said is still not finished.

Undocumented fishers left struggling

Those left undocumented in Ireland by the current system told our team that though workers’ unions were of help, they were often left struggling, with families badly impacted back in the Philippines.

Mark*, a seafarer from the south of the Philippines, has been working in the sea since the mid-2000s. His father was also a fisherman and Mark traveled with him from a young age to help on the boat.

He told us that he left the vessel after a number of months due to improper wages for long working hours — around 70-80 hours per week — which were often double the 39 hours in his contract. “European crews are paid better and get a share,” he explained.

Now undocumented, he is currently trying to obtain permission to be able to work legally in Ireland once more.

When we visited his family home, his wife Lucy* said that “sometimes what he sends is really not enough for us to survive, but what’s important is we’re able to buy rice at least… it’s still better than nothing”.

“His youngest daughter misses him so much. He left when she was just two – she’s now six… He’s been gone too long”, she said.

Mark has not seen his daughter in person for a number of years. Source: Geela Garcia

Mark’s work on the boat in Ireland often began at midnight. “It’s a lot of work fishing for prawns, we get around 4 hours of sleep each day, but that’s only if there isn’t trouble with the nets,” he said.

“There are no jobs here, that’s why Mark went abroad,” his mother Cynthia* told our team. “We are always in touch with him. Every day he says that his life is hard, that he has to [move] from one job or another because his papers are not yet fixed.”

Nobody knows about Mark’s present situation. When neighbors ask why they borrow money, his family lies and says there was a delay in his pay.

Lucy, his wife, added: “When he left, we were expecting that life would be easier, that he would be able to send his kids to school, but what happened was the opposite."

“At least we’re able to get by still. It’s just harder now because the kids are growing already, so that means the costs for raising them are higher as well.”

Mark's mother looks at a picture of her son at their home in General Santos City. Source: Geela Garcia

According to Dr. Maruja Asis, Director of Research and Publications at the Scalabrini Migration Center in Manila, Filipino migrants leave the country for economic reasons.

“They want to improve their family’s lives, they dream for the welfare of the families. Of course, there are Filipinos who wish to see the world, but the biggest motivation is economic.”

We asked the Department of Migrant Workers in the Philippines what it is doing to help people who are being exploited and prevent these practices, as well as a number of other questions. We did not receive a response in time for publication.

Fr Paulo Prigol, Manila Port Chaplain of the international maritime charity Stella Maris, said migrant fishermen are a forgotten category of overseas workers in the Philippines. The sector has been very underreported and understudied.

Currently, there is a proposed Magna Carta for seafarers in the Senate, which hopes to advance their rights on the basis of the International Labour Organization’s Maritime Labour Convention (ILO-MLC) of 2006.

Fr Prigol also said: “The government should craft a law specifically for migrant fishers, because usually when fishers are repatriated they just go home, and go abroad once another opportunity arises. But how best can we help them if the fishers’ only choice is to leave home?"

*Names have been changed

The investigation was supported by Journalismfund.eu’s Modern Slavery Unveiled grant programme. The project team consisted of Geela Garcia, visual journalist in the Philippines, and in Ireland: Maria Delaney, editor of investigative platform Noteworthy, and Louise Lawless, freelance journalist. A series of articles were also published by Noteworthy and can be read here.

- Latest

- Trending