How short stories get written

A reader who liked my short story, “The Riddle,” which appeared in The STAR last Oct. 19, asked if it was autobiographical. I said, yes, but only up to a point. Writers write from their mundane lives and I certainly am no exception. In college shortly after World War II, I had a pretty classmate from the Visayas; she was always well groomed, articulate and very much alive. She was always the star of our college parties because she sang those Liberation songs with such feeling, the songs became her. I presumed that she was from one of the landed families in the South and that she would eventually get married to a wealthy haciendero, too. She was interested in literature and it was this interest which bonded us together. Then before graduation, she eloped and I thought I would never hear about her again, but soon enough, after my first novel appeared, she wrote about how much she liked it. She said she had settled down in sweet domesticity. On a trip to Mindanao aboard one of the small freighters at the time, I found that the boat was stopping in her town to drop a tractor. I decided to visit her. It was early afternoon and a short walk from the pier to her house at the edge of town. I had expected a manorial house; it wasn’t all that poor, but though it was quite big, its nipa roof needed repair. The yard was verdant with ornamental plants and she was there sweeping away the dead leaves. She wore a faded housedress, wooden shoes, and her hair was uncombed; around her, four half-naked children, dirt smeared on their faces. She recognized me immediately, and apparently surprised and embarrassed, she ran up into the house to groom herself. Even before I went up, I already knew that I had a new story.

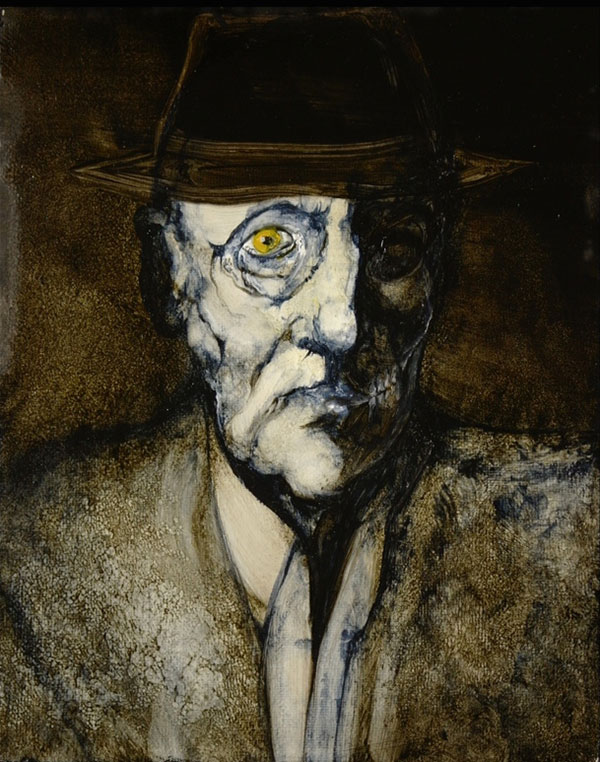

The story in this issue had a different beginning. When I set up Solidaridad Bookshop in Ermita in 1965, an affluent neighbor was an aging magician who called himself, “The Great Dr. Tito.” He entertained children in their parties. He was affable and voluble and once he dropped by the shop to inquire if I had any new books on magic. I had none, and he said I should carry some not just for him but for the elderly who may want to learn a few tricks. “It is all illusion, but the kids think it is real — and so do some adults. It’s cheating,” he laughed, but a nice way to make some money — even when you are already as old as I am…” I started thinking about what he said and soon enough, I wrote this story.

“Hitman for the Apocalypse” by Igan D’Bayan

“Hitman for the Apocalypse” by Igan D’Bayan

MAGIC

by F. Sionil Jose

The Great Professor Faustus is ill and I have to see him before he dies. He is truly a great man even if he did not put that word, Great, before his professional name. I know this and I need not explain for the Great Professor Faustus is my father.

He did not write to me about his illness — he never wrote about his personal problems but even in Manhattan, there were always ways by which a Filipino could get detailed news from his homeland. I was coming out of my office at the Rockefeller Plaza one brilliant November afternoon last year when who would I see disembarking from one of those fat, glossy Cadillacs with tinted windows but my boyhood friend, Claudio, who I used to call Clod.

He recognized me immediately although we had not seen each other for 15 years. He was with a couple of Wall Street types and after effusive greetings, his French cologne swirling around us, I gave him my address and phone number which, he claimed, he had misplaced. He said he had a very busy schedule during his one-month stay in America but the following evening, he was free and asked if I would like to have dinner with him at the Plaza. With his trim grey suit and the air of prosperity about him, he must have won the Manila sweepstakes. It was so unlike the Clod that I knew, who became Father’s assistant when Father realized that I would not take after him.

His suite consisted of an anteroom and a bedroom as wide as a church. We had dinner brought in — Maine lobster, artichokes, German wine — and while we were eating, he told me about his good fortune that evolved only during the last 10 years or so.

“I owe it all to the Great Professor Faustus,” Clod said, gratitude shining in his eyes. “Without him, I would not be the successful healer that I am today.”

He then went into a joyous account of what had transpired in the last decade, how faith healing and psychic surgery had become big business in Manila and how it attracted the wealthiest clients from Europe and the United States. They even came, he said, by chartered flight. “All this stay here in America is already paid for and, of course, there is a big bonus when I leave, with or without cures.”

Having been my father’s assistant, he had learned the tricks of illusion. Now, he applied them with such finesse he himself was amazed at the cures he had administered. I suspect that with his lofty enthusiasm, he had come to believe that he actually possessed healing power.

“I told him to go into faith healing a long time ago,” Clod said. “It is not disreputable in Manila anymore. The best people come to me — politicians, wealthy Makati businessmen and, would you believe it! Even the generals, and their wives and mistresses...”

“What did Father say?” I asked. He had pushed aside the lobster and said it could not compare in taste with our own spiny crayfish.

“You know your father,” he said with a hint of sadness. “He belongs to a bygone era. He is old-fashioned. He said he creates illusions to make people happy, to make them forget their problems.” He shook his head. “He said he was not meant to cure illness. That was the doctor’s job. Or God’s.”

For all his chicanery, there was something still honest about Clod. “I think you should go home and see him,” he said afterwards. We were having our dessert of chocolate cake, brie and coffee. Outside, the lights of Manhattan burned bright in the crisp autumn night. “I will tell him I saw you. I saw him sometime ago — and I knew he was not well.”

It was not only Clod whom Father had helped. In our neighborhood in Mandaluyong, people knew him not just as a magician who performed tricks that bordered on the incredible, but as a man whose house was open. If only he knew how to close his door once in a while.

He was a bad correspondent. I often chided him for not writing more often. In the few instances that he did, his tone was always jovial, often hilariously so. When Martial Law came, he never wrote about its excesses which the American press faithfully reported. It was not fear which inhibited him; it was just his nature.

He even joked about the regime and I imagine he must have relished telling this story as if he were still on the stage of the old Savoy or the Palace where he got top billing shortly after the war when vaudeville and the stage show were already dying.

He was on this elevator and there was only one other passenger. He asked him if he was from Leyte and the man said no. He asked the man again if he was from the Ilokos, and again, the man said no. Finally, Father asked: “Are you in the Army or are you related to any sergeant or officer?” Again, the man shook his head. At this point, the Great Professor Faustus gained some courage and he told the man. “Then, will you please take your shoe off my foot? You are hurting me.”

He had a way of putting himself in his jokes, his audience easily believed they really happened.

My earliest memories were those of his sleight-of-hand tricks, his soothing voice that rose to a crescendo as the climax to his act came, like freeing himself from tightly knotted ropes, or making his tall black hat explode in a flash. Those were the days I spent in sweaty backstages where, beyond the footlights, I could see the rapt faces of people, their long applause sweetly drenching me, for this man — my father — now bowing on the stage, had relieved them for an instant of their anxieties.

There was a woman, too, who was beautiful as all of Father’s women were, particularly when they were on the stage decked in the finery of showbusiness. At first, this woman doted on Father; she did his bidding eagerly, cooking our meals, washing our laundry. But she lasted only so long as did the others. I thought she was my mother then but she was really just an assistant to the Great Professor Faustus and, like the rest, she left when she found a better job or, as I was now inclined to believe, when she lost interest in magic.

Father never really talked about my mother although I often asked him. He was always evasive and had a stock answer, that in some future time, I would see her. He said she left him and was careful to say it was not I who was the reason. “It was all my fault,” he would add, a wistful look on his face. “Perhaps, I have been too importunate, too careless. Perhaps, I was not able to give her all the things she wanted. Happiness, most of all.”

“You should always love your mother,” he said.

It never occurred to me to doubt him. Why should a father lie to his son? It would be like lying to oneself.

But if I did not know my mother at that early age, I had a whole flock of aunts — itinerant women — who attended to me, who performed on the stage with Father, who were often at home partaking of our food. He never remarried.

We were more fortunate than most of his colleagues, the snake charmers who had to work the street corners with their panaceas, the chorus girls who went down the abyss and sold their bodies, and the other magicians like Canuplin whom Father helped although they were his competitors.

For one, Father had this small, weed-choked lot in Mandaluyong with a wooden frame house which he inherited from his parents. He had difficulties during the rainy season when his appearances were limited to household parties of the rich and in school and office parties.

When I started going to school, Father spent more time with me although he was often away, appearing in town fiestas. He used to stay up nights washing my clothes. He told me at that early age that it was in the United States where I should someday go because I was good at math and there, I could escape our poverty. It was a dream I shared with him and it came true when, in college, I won a fellowship at MIT.

So it was — 15 years in America. The first five of those were dismal because my scholarship was barely enough and Boston winters could get very severe. But because I also worked with my hands, something which Father always urged me to, I was never hungry. It did not seem possible for anyone to starve in America for as long as one was willing to take any kind of work.

After college, it was the Big Apple where the competition was keenest. There was a saying among Filipinos that if you could make it in New York, you could make it anywhere. I had no difficulties, however, for in my last year in college, even before I had my diploma, I was already recruited by my company. It was quite an easy climb for aside from being highly qualified, I worked hard, determined never to know again those days when Father and I had only scraps of fish, or tuyo, because he had no engagements. Not once was I depressed. I often recounted one of those ethnic jokes, perhaps Polish in origin, how Filipinos in New York, no matter how miserable, could never commit suicide because they all lived in basements.

I did try looking for Mother without the slightest notion where she would be, or if she was still alive. I introduced myself to the oldtimers as the son of the Great Professor Faustus. Some remembered him but no one ever heard of his wife.

In retrospect, I realized that my motherless childhood had affected me. I was not shy and I was certainly no misogynist but I was scared of developing lasting relationships with women. The psychological block did not persist, however, after college. In New York, I met Jane. She came from a small town in Illinois — Elgin — where they used to make those watches which Father said were very expensive and popular in his time. Her father was a doctor and their brick house was still there where her parents lived.

Jane had green eyes, freckles and a perfect nose. I did not intend to get serious with her. Like some Filipino males, I had planned to return to Manila, meet a girl then marry her. I knew well enough the pitfalls of marrying someone from a different culture. On the other hand, I had heard of the traumatic experiences of oldtimers in Hawaii and California; in their sixties, they returned to the Ilokos to marry young girls, bringing with them their life savings as dowry. When they returned to Honolulu or San Francisco, they were dumped by their brides.

Father said I inherited some of Mother’s features, her imperious manner and imagination. I even told tall stories about my background which I had to rectify later. I told Jane, for instance, that Father was an engineer, too. She did not press me for details. If she did, I would have elaborated and said Father was a social engineer — whatever that was, and his work was anchored on a belief that he could provide joy or, at least, a few laughs that would divert people from the malaise of the world. In truth, that was what Father believed in.

There was that year we had little food; the euphoric days of Liberation had passed, vaudeville was dead. At times, he brought home a small brown paper bag with a couple of shrunken siopao which, for me, was a feast. There was no one in the house to cook and he did not want me to do that. He would watch me eat and I was too dense to know then that he had no supper yet. Or when he had some money, he would lend most of it to friends in the profession, knowing he would not get it back.

His jokes from that period were about Magsaysay whom he liked very much. One I remembered had the Great Professor Faustus as a farmer. He had gone to the President to complain about the artesian well which the President had set up in his village. For three days, he waited in the Palace but could not see Magsaysay; he was always out in the provinces jumping over ditches and shaking hands with farmers. Finally, Magsaysay arrived and Father went to him and said:

“Mr. President, you remember the promise you made in Barrio Likut?”

The President said, “I always make promises. What did I promise you?”

“An artesian well, Mr. President.”

“You got it, didn’t you?”

Father replied, “Yes, Mr. President. We have the artesian well but we don’t have water.”

The President looked at Father balefully and said, “What are you complaining about? I promised you an artesian well. I didn’t promise you water!”

So here I was, 15 years in America, with an American wife and a seven-year-old son both of whom I would someday bring to Manila to meet the Great Professor Faustus. Watching my boy grow, I recalled how it was with Father. I did not think I was remiss in my filial duties. Even when I was just making a few dollars in part-time jobs and in the summers in Boston, I was already sending him money. And when I finally went to New York for the job I was suited for, I sent him a good sum every month. Jane also had a good job. She was a biochemist and she understood what I was doing and asked if she could help, too.

I had told her we had no retirement schemes in the Philippines, that Father needed the money not just to live on but to rebuild our house. More than anything, I was worried that since he was no longer working regularly, he was not eating well.

There were opportunities for me to go home but I missed them. One evening while working late in the office, I thought about the trips that I had missed and was both shocked and surprised to find that I did not really want to go home, that somehow, I would no longer fit.

I had already become an American citizen and had petitioned Father to come to New York and live with us but he refused. He also had not written in three months and there was no telephone in Mandaluyong so I could call him. Then his letter came. It was so perfunctory, so unlike the old letters that were full of life. Clod confirmed it — the Great Professor Faustus was ill, perhaps dying.

I did not realize the extent of the Philippine government’s program of enticing Filipinos to return to their homeland to see how Martial Law was. At the Chicago airport where we had an hour stopover, I saw how successful it was when the plane that November afternoon was simply filled with countrymen with mountains of homecoming packages. It was pure bedlam. I never had much dealing with my countrymen. In my company I was the only Filipino professional, except for a couple of secretaries from Cebu. Now, in the plane, it was hometown week. I sought out the older people. Many of them were from the sticks, from the Ilokos. The few who had lived in Manila hardly remembered the old Clover Theater or the Savoy. No one ever heard of Father.

We arrived in Manila at about eight in the morning. Even before we sighted land, I was already eagerly looking out of the window till the familiar terrain appeared below, the green mountains, the green seas, the green fields turning yellow with the rice harvest.

As we eased down, I was amazed at the many new buildings to our right — the Makati that had burgeoned the last ten years. But the airport was, as before, a dismal cauldron of officious clerks, hustling customs examiners, and pugnacious people who had no business there. Then they started coming out — the huge boxes that the balikbayans brought as homecoming gifts. And here I was with just two suitcases. I was not going to be Santa Claus to some six dozen relatives. There was just Father and one suitcase filled with things for him, even a new book on magic which I bought at Doubleday’s before I left New York.

I squeezed out of that steaming airport and looked in vain at the straining crowd beyond the wire mesh fence for Father. I had sent a cable and there being no one to meet me served only to heighten my apprehension.

A phalanx of touts met me at the exit and if I had been one of those old provincianos, I would have been easy prey. I made it clear that I was no balikbayan. The taxi driver seemed disappointed that I knew exactly where I was going.

There were real changes. The streets were cleaner, unlike what I remembered — the piles of garbage on the sidewalks. Smiling Martial Law, Martial Law Philippine Style. Only a handful of soldiers at the airport, no tanks, no sentries and barricades in the streets. And Makati — all those stone monoliths and how big the acacia trees had grown.

The traffic was also worse. The cab rocketed through rutted streets once we left the highway. Finally, the old tattered neighborhood, the same unpaved dirt road and on both sides, wooden houses falling apart, laundry hung like buntings on the windows, children everywhere, the scab of years unlifted.

Then, our house. I had expected a new one — large and good enough for an American family to come home to. The lot had not been cleared of weeds and was not even planted to pechay and other greens the way I did it. Beyond the mossy adobe wall, our old battered house. The door was open.

Father must have seen me push the iron gate, complaining loudly at the hinges, for now three boys came rushing to grab my suitcases. I let them. He came out then in his old silk pajamas which he wore when he had important visitors. The creases of the folding were still visible. How old Father had become; his hair was now all white and wrinkles ridged his face. But the eyes — they were as cheerful as ever. He walked towards me with faltering steps. I kissed his hand then embraced him. His eyes had misted. He was full of questions, how the trip was, the grandson he had yet to see.

The neighbors trooped in — Mang Enteng, Aling Julia, Ka Edro. the narrow living room was soon filled with people and some had to stay outside while I tried to speak to everyone so that they would not say that this Americano had become snooty. I had not expected so many welcomers and though I had a suitcase for Father and some gifts in it, I did not have enough for everyone. A couple of Parker ballpens, a dozen plastic playing cards, two cartons of cigarettes and two bottles of tax-free whiskey. I did not dare give out any until I had consulted with him.

We were finally alone in the bedroom after lunch which Aling Julia had cooked. Outside, the sun blazed down and I was burning with the heat of the tropics. I was also annoyed that not a single improvement was done on the house in spite of the money that I had sent.

The rigor of welcome must have tired Father; he lay on his iron cot breathing heavily. How he would have changed if only he came to America; the fresh milk, the cartons of orange juice — in a couple of weeks, there would be color to his sunken cheeks and this despondent glaze over his eyes — the handiwork of age and living poorly — would be gone.

“I can see why you don’t want to leave this place,” I told him, recalling the neighbors and the children. He used to have me call all the kids on Sunday afternoons and in the yard, he would show them the old tricks that never ceased to amuse them.

I couldn’t repress my disappointment at having to return to the old house to which I could not bring my family — not while it was run-down like this. I asked it then. “Papa, what did you do with all the money that I sent you? I thought you would have the house rebuilt like I told you. There was more than enough money, wasn’t there?”

He ignored my question. He sat up slowly, gazed at the faded posters on one side of the wooden wall, posters about the Great Professor Faustus at the Savoy, the Finest Magician in the Far East, the Miraculous Soothsayer. When he turned to me, his eyes were aglow. “I have a new trick,” he said. “I have spent almost a month just thinking about it. I should try it on the children this Sunday.”

It was the old ruse he used when as a boy I asked him where Mother was.

“It is difficult,” he continued. “It requires strength which, fortunately, I still have a bit. I go up the stage, manacled you see. Then, there is this sack...”

I had not intended to sound angry. It must have been the long haul from New York, the cramped conditions in the 747, the stinking toilets and that mob at the airport. It was also stupid of me to have suggested an accounting knowing that he always held the view that money should go around like fertilizer if it must do any good. All the neighbors, the children, I was sure, had benefitted from what I had dutifully sent. I no longer needed to give them homecoming gifts.

No one needed to tell me that tile roofs, narra panels and floors did not make a home but I had expected to see something substantial for all the years that I had worked so hard. Or, perhaps, I had lived too long in America.

“Stop it, Papa,” I said. “I am no longer a boy and I am not looking for Mother anymore. I have already found her!” The smile fled his face. His eyes widened not so much in surprise, I thought, but in fear.

“Yes?” he asked weakly. “You saw her?”

I shook my head more in regret than in anger. “That was not what I meant,” I said. God, it was warm. The heat seemed to bury me under its white fury. “I meant I have realized why she left you.”

He raised his withered hand in a gesture of protest then turned away.

“You have not changed, Papa” I said. “You are stilI the same. Can you not see how times have changed and so have I? But you act as if time had stopped. The Clover is no longer there. Before I left, it was already torn down and made into a parking lot. And so is the Savoy. And Canuplin who was your friend...”

I could not go on.

He stood up, he limped but there was stilI some sprightliness in his frame. He raised his hand again as if he was on the stage, acknowledging the adulation of the crowd. He did not face me as he spoke. “So times have changed. So there are many things which I never told you.” He shook his head then, almost in a whisper: “I did not tell you about that wonderful night in Dagupan — the big audience that saw me. And your Mama — she was six months on the way — that was you, and we fooled them all, as if she was a young girl with her make-up. They really loved her...”

I think my voice leaped when I said, “Stop it, Papa,” again. “I don’t want to hear anymore about what you did, about Mama. You don’t have to explain to me. I knew why she left you. You always wanted to please people, to make them forget what was real. But the world is real and it is not kind. People are ungrateful. And you wasted money. What now are left with you but these — these faded posters!”

He turned to me then. Thinking back, he must have known just what to say at that precise moment. “Memories,” he said quietly, then limped back to the old rusting bed and sat down. Tears rolled down his cheeks so I went to him and embraced him.

I left for New York after three days. I had all sorts of explanations for the brevity of my visit — the awful weather, the heavy work load that I left. I was homesick for Jane, my boy. I lied to everyone except myself.

All their lives, people go around looking for happiness. Perhaps I will find it in America, in the plenitude that is at my fingertips. I don’t know. I do know that Father lived happily even after Mother had left us, no matter how run-down the house, no matter how grasping the neighbors and ungrateful his friends.

I am a loyal son, but I cannot go home again.