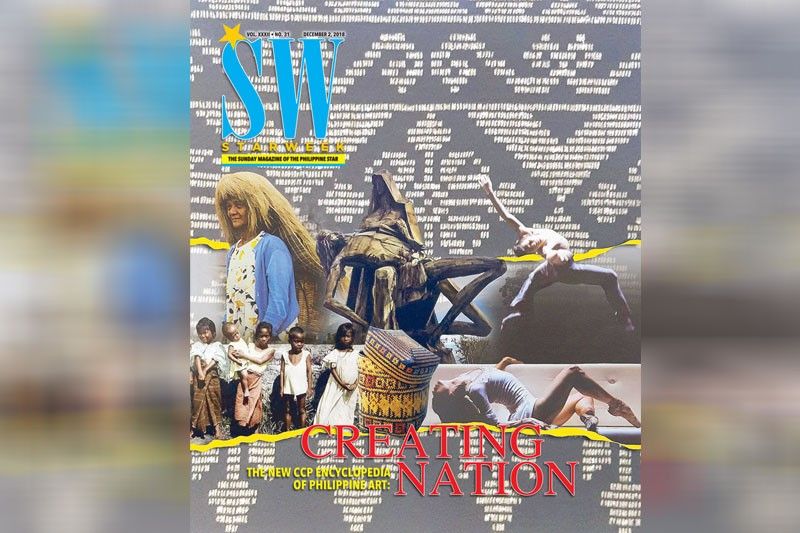

The new CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art: Creating Nation

MANILA, Philippines — Hard copy encyclopedia sets are like dinosaurs from another age. They aren’t extinct yet, though. While some revered publications such as Encyclopedia Britannica have turned soft, there are still some that are alive and kicking and continue to thrive on library shelves.

At the Cultural Center of the Philippines Library, which is renowned for its collections on arts and culture, it is the CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Arts – fondly referred to as EPA – that is most sought after by students and researchers.

CCP Library director Alice Estevez points to its uniqueness as the reason for its fabled status. It is one of a kind.

CCP Library director Alice Estevez points to its uniqueness as the reason for its fabled status. It is one of a kind.

According to Estevez, it is the first thing that people look for when they step into the library, People ask: Where is this CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art that we have heard so much about? And they are just so delighted when they see it, she says.

Published in 1994, countless hands have leafed through its pages, making it among the most battered and dog-eared books in the library. At the National Library, Esteves reports, the CCP EPA is in near tatters.

“It is really used!” editor-in-chief of both the first and second EPA, Nicanor Tiongson, says.

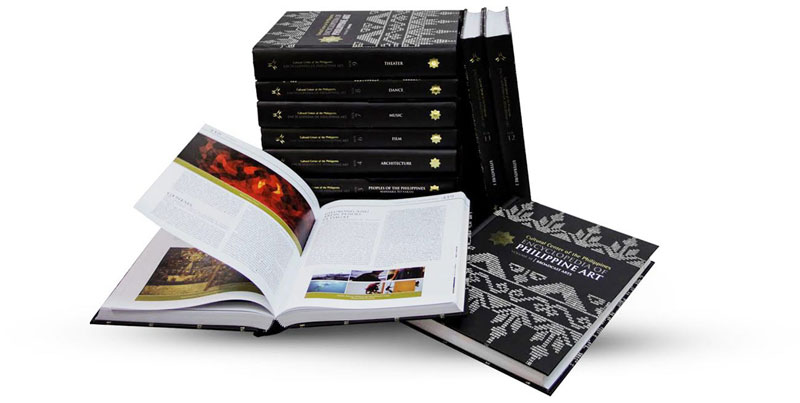

The EPA volumes make for a hand- some box set

The EPA volumes make for a hand- some box setTiongson cites the one time a researcher asked the Agta people for material on their tribe and they handed him a copy of the entry on them from the CCP EPA.

“They use it to prove their identity. It validated their existence. Malaking bagay yun (That’s a big deal)!”

Last Thursday, more than a good two decades after the first edition came out, the CCP launched the second edition of the EPA, in print format to be followed by a digital version soon.

CCP artistic director Chris Millado, who served as the EPA second edition project manager, describes the CCP EPA in the foreword as “ an important compendium of data on Philippine art and culture for all generations. The second edition enters the new millennium cognizant of a generation of content consumers that are quick to adopt the latest trends in technology, have great access to information and are globally connected.”

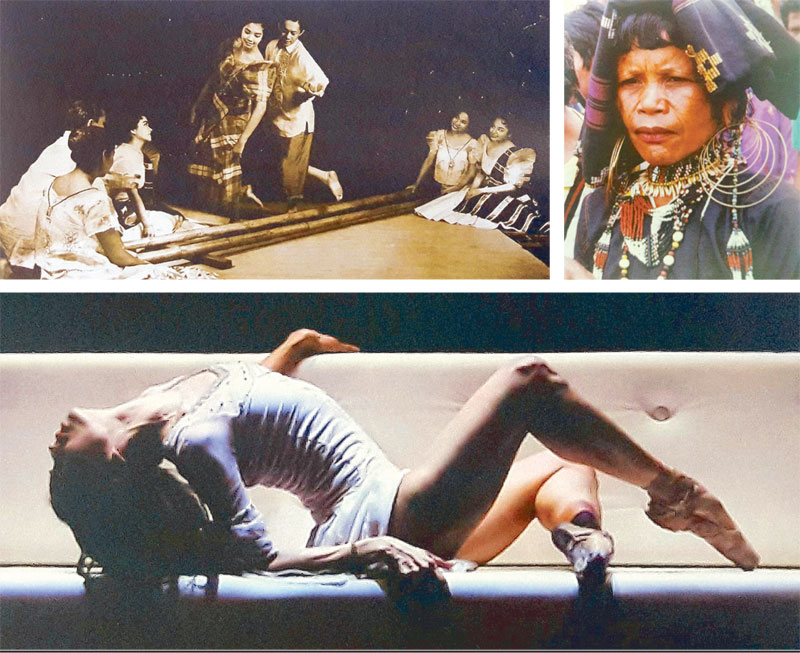

ART-I-FACTS :A jewelry bedecked woman from Sultan Kudarat; David Campos’ The Sleeping Beauty; Ricar- do Reyes with daughter Alice Reyes, now National Artist for Dance, performing the tinikling. On the cover: Images from the Philippines’ rich cultural history found in the pages of the encyclopedia. In the background is the black and white weave featured on the cover of each volume of the EPA.

ART-I-FACTS :A jewelry bedecked woman from Sultan Kudarat; David Campos’ The Sleeping Beauty; Ricar- do Reyes with daughter Alice Reyes, now National Artist for Dance, performing the tinikling. On the cover: Images from the Philippines’ rich cultural history found in the pages of the encyclopedia. In the background is the black and white weave featured on the cover of each volume of the EPA.The idea of a second edition was hatched in 2005 when CCP president Nestor Jardin asked Tiongson to lead an evaluation of the first edition. The real work, however, started only in 2013. It took five years to complete, P45 million to fund and an army of editors, writers and researchers to finish it.

Just recently, Millado showed a millennial the new set just to see how he would interact with the books.

“It had a wow effect!,” Millado recounts. “And he (the millennial) pulled out one volume and exclaimed,‘Wow, it is heavy!’”

And by heavy, Millado would like very much to mean not just heavy in weight, but a heavy weight in terms of content.

The last two decades have been extraordinary, in terms of art making, Tiongson says. And because of the increase in artistic production and new research and data, the new CCP EPA has grown bigger and, yes, literally, heavier.

The new EPA has 12 volumes, two more than the first edition.

“Since the publication of the first edition,” Tiongson writes in his introduction, “a wealth of research data has been unearthed by scholars on all aspects of the Philippine arts.”

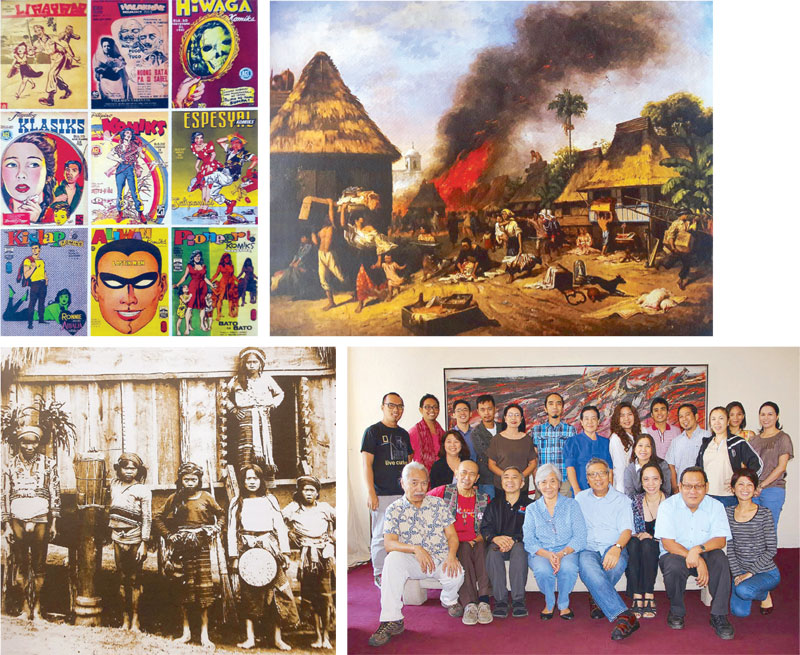

FROM THE PAGES OF THE EPA (clockwise from above): An Apayao family; komiks cover art; El Fuego (1889) by Lorenzo Guerrero; the team behind the monumental work with editor Nicanor Tiongson (seated, fourth from right).

FROM THE PAGES OF THE EPA (clockwise from above): An Apayao family; komiks cover art; El Fuego (1889) by Lorenzo Guerrero; the team behind the monumental work with editor Nicanor Tiongson (seated, fourth from right).The CCP EPA, both in the first and second editions, cover The Peoples of the Philippines (three volumes, up by one from the first edition), Architecture, Visual Arts, Film, Theater, Dance, Music, Literature (two volumes). The newest addition to the second edition is the volume on the Broadcast Arts.

Written by scholars and researchers, the CCP EPA offers users information that is verified and acceptable as citations in scholarly papers and literature. It presents a wealth of details and facts about Philippine arts and culture. A total of 821 writers worked on the books that contain a total of 5,352 entries.

All existing entries were updated and new ones were made based on a criteria established by the editors.

In The Peoples of the Philippines, for instance, there are three new additions to the ethnolinguistic groups. These are the previously unstudied Ifiallig, Agta and Agta Manobo.

Tiongson reveals that many writers who contributed to the volumes on Peoples were members of the ethnolinguistic groups and wrote with an insider’s perspective.

Tiongson made sure that a people-oriented view was taken in writing the individual histories of the various groups. The oppression and marginalization of these groups, according to Tiongson, affected their art making. Developments such as mining and deforestation has led to their displacement and caused their art forms to die.

In the Architecture volume, the conservationist agenda of the CCP EPA is very evident.

“We want to call attention to these buildings. They are important and they should be preserved,” Tiongson stresses.

Rare postcards depicting the edifices from the American period were used. Tiongson says, “I want people to have a memory of how the original buildings looked before the war and that Manila was such a beautiful city.”

The use of full color pictures, and lots of them, is what distinguishes the second edition from the first where photos were printed in two-color brown tones. The ratio of entry to photograph, in the new edition, is one-to-one.

Visual researchers who worked on the new edition faced a monumental task. The hunt for photographs was particularly difficult in the area of broadcast arts. The reason, Tiongson cites, was that radio and TV were not considered art for the longest time.

Radio drama scripts were thrown away just like that, he says. The old photo albums kept by Tiya Dely, a well-loved icon of Philippine radio best known for the advice she gave listeners, was a treasure trove of pictures that found their way to the pages of the CCP EPA.

According to Tiongson, the Broadcast volume is very valuable. It is the only sourcebook, complete with entries on all the important TV and radio programs. It also contains the long history of broadcast media. It is the first of its kind and the most scholarly and comprehensive.

For subject matter where there were no photos to be had, art work was specially commissioned to illustrate the books, particularly of the literary traditions such as the folktales of the various ethnolinguistic groups.

The CCP EPA sought to demolish the division between the fine or high arts and the low arts.

“The CCP EPA editors are from the academe and the bias is for legitimate art, but we decided against that in the spirit of change that the CCP started,” Tiongson reveals.

“You cannot have a bias against popular art forms. And so you find Komiks in the EPA and it is treated on the same footing as all other art forms. You have radio drama and TV and all are considered equal as legitimate ways for the Filipino artists to express themselves.”

Thus, in the volume on music, one can read about hip hop and rap, Pinoy rock’s Ang Himig Natin and OPM. In the dance volume, ballroom, cheer dance and even aerobics are found along with ballet and folk dance.

The CCP EPA is also gender sensitive. In film and broadcast, breakthrough works were included, for instance, those in the LGBT genre. Entries such as “My Husband’s Lover” and the first gay programs on TV can be found in the Broadcast volume.

Millennials were a major consideration in the making of the new CCP EPA and are precisely the reason why a digital version is in the works, slated for release in 2019.

“The digital edition will contain all the text and pictures of the printed edition and much, much more because it will be able to post more illustrations and, more importantly, incorporate video clips showing excerpts from major works in dance, music, theater, film and broadcast arts as well as the documentation of heritage buildings, Tiongson says in his introduction.

In the beginning, only a digital version was planned. But Tiongson and his editors all argued for a print version and, thankfully, won.

Millado, who was the chief advocate for the digital version, recounts: “Initially, I didn’t want a print version. Everything’s being migrated to digital platforms. Tiongson called me a book burner and threatened that they would not do this if it would be just the digital version. They said there is still value in print. I had the suspicion that they were holding to the idea of print because of a romantic attachment to books. But I was happy to be proven wrong!”

When the hard copy EPA was announced early this year, 1,500 sets were immediately sold, with the University of the Philippines claiming 1,000 and the Department of Education 500 for its public schools. Many individual reservations have also been made. “I foresee that we will be sold out, if not this year, next year and we will get orders for reprints,” Millado predicts.

The journey in making the new EPA has really been an epic quest.

Tiongson, though he never entertained the thought that it would not see fruition, confessed that he would pray to National Artists Atang de la Rama and Lino Brocka for the books to be done with and finally see print.

More than anything, the EPA, he asserts, is the CCP’s contribution to the creation of the nation as an imagined cultural community.

Citing Benedict Anderson’s concept of Imagined Communities, Tiongson elaborates on the vision of the EPA that it contributes to the creation of nation.

“With the entries in the EPA, you are actually saying these are important to us and that the definition of Filipino depends on those entries. All cultural traditions and art forms are included. The CCP EPA contributes to shaping a nation and a consciousness of what Filipino means.”

For inquiries and reservations, contact CCP Marketing (tel 832-1125 loc 1803) or visit www.culturalcenter.gov.ph

- Latest

- Trending