Notes on some scandals

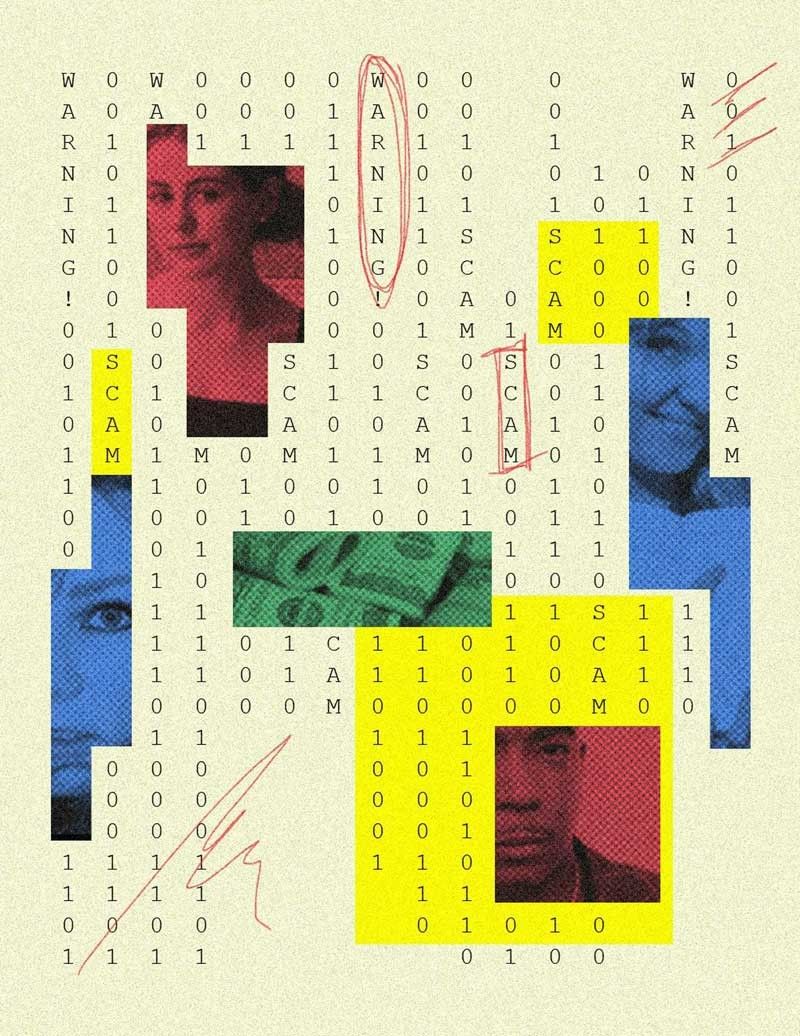

What is it about the internet that makes people so eager to commit — and uncover — false narratives and forged identities?

In 2017, the internet was lit ablaze when tweets began to surface from people who were quite literally stuck on an island. Lured by the promise of Fyre Festival, an ultra-exclusive music event that doubled as a luxury vacation to the Bahamas, they were instead met with rain-drenched emergency tents for shelter and stale sandwiches. There was no music festival, and with hundreds of guests and zero return flights booked, there was no way for them to leave.

Everything was on, well, fyre, and nobody could look away.

It was a gratifying thought: influencers and rich jerks had been fooled. As told by the Netflix documentary Fyre: The Greatest Party That Never Happened, however, the mess was worse behind the scenes — it was a front for Fyre CEO Billy McFarland to pocket millions of dollars in ticket sales and investments, for which he’s been found guilty of fraud.

Many other tawdry schemes have made headlines in the months since. It has happened consistently enough that Vulture began calling it the “Summer of Scam,” which then bled into the “Winter of Scam,” which then became the all-encompassing “Year of Scam.” It’s only apt that Melissa McCarthy recently earned an Oscar nomination for her performance in Can You Ever Forgive Me? as Lee Israel, a biographer known for dabbling in literary forgery to revive her failing career.

Lani Sarem is also an author who went to great (fallacious) lengths to get to the top. Her debut book Handbook for Mortals went straight to number one on the New York Times list for bestselling young-adult hardcovers upon its release in August 2017, yet very few people had actually heard of it. It was eventually removed when it was discovered that Sarem had gamed the system and “fluffed up” the sales numbers by placing bulk orders for the book in different bookstores, which reportedly reached a total in the 10 thousands.

Another writer was Rose Christo, whose then-forthcoming memoir was bound to shake up pop culture because part of it was about an infamous piece of Harry Potter fan fiction — My Immortal. The true identity of its author, “Tara,” had been unknown for the longest time, and now it was entirely possible that she was finally coming forward in the form of Christo. But in October 2017, the memoir was shelved, because she couldn’t provide sufficient evidence for her claims.

In April 2018, Rachel DeLoache Williams wrote a Vanity Fair piece on Anna Delvey, a socialite who lived in a four-star hotel in Manhattan and dreamt of setting up an art foundation. They had gone on a trip to Morocco, where Delvey made Williams’ $62,000 disappear in a blinding haze of shopping sprees and luxury accommodations. It turned out that she was a fake heiress, a con artist who cashed in bad checks and “borrowed” money from friends that she never fully paid back. Since her story emerged, two separate television adaptations of Delvey’s life have been in development: one from Shonda Rhimes, and another from Lena Dunham.

The poetry side of Twitter had a field day when, in December 2018, poet Rachel McKibbens posted about an email she got from Ailey O’Toole, whose poem was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. O’Toole wrote in her email that she it had “slipped (her) mind” that a stanza from her poem was actually “paraphrased” from an earlier work by McKibbens. (The line was tattooed on O’Toole’s arm.) Since her admission, more writers have come forward with allegations that O’Toole had also plagiarized their work.

The latest in the string of alleged scammers is Caroline Calloway, an Instagram influencer who had been charging $165 for a series of “creative workshops” that would take place in various cities. The workshops were evidently not planned very well: Calloway neglected to book venues and asked guests to switch cities; many “perks” and scheduled activities failed to live up to expectations or materialize at all; and attendees were made to sit on the floor. She even admitted that she no longer wanted to cook the homemade lunches she’d promised her fans and instructed them to bring their own meals instead.

On the internet and social media especially, we tend to present a neater, if not idealized, version of who we really are. We can choose which parts of our lives and identities to share and which ones to omit. For most of us, it’s not so different from how we normally present ourselves in real-life social situations. But for certain people, the tendency to turn our profiles into “highlight reels” becomes both aspiration and inspiration — because it all happens on a screen, it feels virtual, and only further compels them to bend the truth for likes, or status, or even a shortcut to success. After all, who could ever know?

The flipside is that the internet has also proven highly useful for investigating the glaring inconsistencies that fuel our doubts and unraveling these stories. From amateur sleuths to professional reporters, people have been coming together online with reverse image searches and other information they’ve dug up for a 360-degree view of the situation, where one small piece of the puzzle becomes a lead to another, and another. This was how Sarem, O’Toole and Calloway were exposed.

Maybe the question isn’t why these things keep happening, but why we keep paying attention to them. What is it about them that makes them so newsworthy, and why are we so fascinated and outraged? There are of course the bizarre “Wait, it gets better” details, like Sarem’s book essentially being badly written fic for Twilight star Jackson Rathbone (whose band she managed) or Calloway being overwhelmed by the 1,200 mason jars she ordered for her workshops.

More than that, though, it’s that these scammers thought they could lie, cheat and steal in admittedly creative and devious ways and suffer no consequences or never get found out. It’s trying to understand and see how they even got away with it for so long. It’s messed-up behavior, but that’s what’s interesting about it. There’s something about the hubris, the desperation or delusion, and the sheer amount of effort that goes into creating and maintaining a made-up world or persona.

That, and it’s always nice to know how much we still value authenticity — and to protect some realities in this post-truth world.