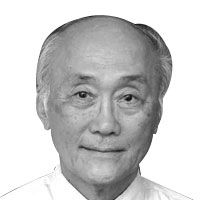

Manuel A. Roxas, transition and rehabilitation president

The man whose picture graces our blue-colored P100 bills is Manuel A. Roxas, the first president of the new Republic of the Philippines. He was the fifth Philippine president, if, as some historians count, we start with Emilio Aguinaldo.

On April 15, 1948, he died of a stroke. Today’s column is a fitting reminder of his place in our economic history.

The force of historical events. As the elected one by the people to preside over the first years of the new republic, Manuel Roxas was destiny’s child. The country’s future prospects were for him to shape. He was inaugurated as our own Philippine flag rose and replaced the American on July 4, 1946.

In the presidential election of April 23, 1946, Manuel A. Roxas won over Sergio Osmeña, the successor to Manuel Quezon as Commonwealth president.

Unfortunately, Roxas was to serve as president of the republic only for less than two years of his four-year term, for he died while in office.

The leaders of the new nation, beginning with Roxas, had to wrestle with the dominant forces of influence and control that the former colonial master had on the nation’s future, despite independence.

To begin with, the Tydings-McDuffie Act – the Philippine independence law – had already set the independence date to be July 4, 1946. Immediately after the war, there was a joint understanding, with the assent of Washington, of course, that the schedule of independence was to be respected.

The need for reconstruction and economic recovery. Manuel Roxas was an outstanding member of the generation that secured Philippine independence from the United States.

In a sense, Roxas presided briefly over the “politics of colonial consent and sovereignty” that was to engulf the newly independent republic.

Those in charge of the newly independent nation took office at a great moment of weakness. The economy had been badly mangled and decimated by a destructive war, and had suffered further great loss of human capital that was essential for undergoing a seamless transition toward full independence.

Nothing now was seamless and made to order as was originally contemplated in 1934 when the grant of independence was decided after undergoing a 10-year political transition period as a self-governing commonwealth.

A war had ruined that transition.

The first major task of the new president was to put in place a program of economic reconstruction and growth. The country had practically no financial resources of substance to work with to undertake that reconstruction.

The politics of consent and sovereignty. The months of May to June were hectic periods of political maneuverings within the newly constituted government, prior to the transfer of sovereignty.

Manuel Roxas made a visit to the United States as president-elect to drum up support for economic assistance. The country simply needed external help even much more than other nations who had also suffered from the war. He stressed that the Philippine economic progress was for the nation to succeed and that this was also in the US interest.

He secured budgetary assistance to sustain the fiscal problems of the new government. (budgetary loan, plus remittance of prewar taxes on Philippine coconut oil refining in the US that were escrowed in the US Treasury.)

The former colonial master committed to put up resources to finance a program of rehabilitation for the new republic. This was part of its grand strategy as former colonial ruler, and recent victor in a great world war.

Two new important laws in the United States were enacted handily and quickly just one week after the Philippine presidential elections took place.

The first law was the Philippine Trade Act of 1946 [or Public Law No. 370, 79th US Congress]. This legislation spelled out a period of economic adjustment in the relations of the United States with the new republic.

Though this law took into account the recommendations of the Joint US-Philippine Commission, which was composed of American and Filipino commonwealth government officials, and updated for later developments, in the end, it was a law made in Washington DC.

One of its major provisions struck at the heart of a provision of the Philippine Constitution of 1935. It required that Americans be given the same treatment as the nationals of the Philippines. This meant equal treatment, or parity, with the rights of Filipinos.

Actually, the US State Department was in sympathy with the Philippine position on this issue. But American property interests in the Philippines made sure their sentiments were felt by US legislators and won in the final version of the law.

This problem became a central point in the new, emerging relations with the United States. To accept the provisions of the new trade act would require an amendment of the Philippine constitution.

The second law was the Philippine Rehabilitation Act of 1946 [or Public Law No. 371, 79th US Congress]. To a badly destroyed country, economic assistance was important to bring the country back to its feet. This second law appropriated a sizable amount of money to finance the economic rehabilitation. It was based on a study of the war damage suffered during the war covering public facilities and private institutions and property.

Practical politics meant pragmatic decisions to overcome obstacles when in the way. The major choices open to the newly elected leaders were clear and limited.

Accepting the provisions of the trade act would set in motion the availability of rehabilitation funds as well as trigger the resumption of trade and economic relations that existed prior to the war in which major Philippine industries had access to the American market.

At home, President Roxas fought for the political acceptance of these terms through congressional action. In spite of strong opposition to acquire the three-fourths majority, the government managed to secure a narrow vote in its favor.

The question of parity rights for American citizens was later put forward in a direct referendum to voters. Roxas’ government staked its leadership to approve it, and the country approved the referendum. To be continued.

My email is: [email protected]. For archives of previous Crossroads essays, go to: https://www.philstar.com/authors/1336383/gerardo-p-sicat. Visit this site for more information, feedback and commentary: http://econ.upd.edu.ph/gpsicat/

- Latest

- Trending