Leaving the familiar behind

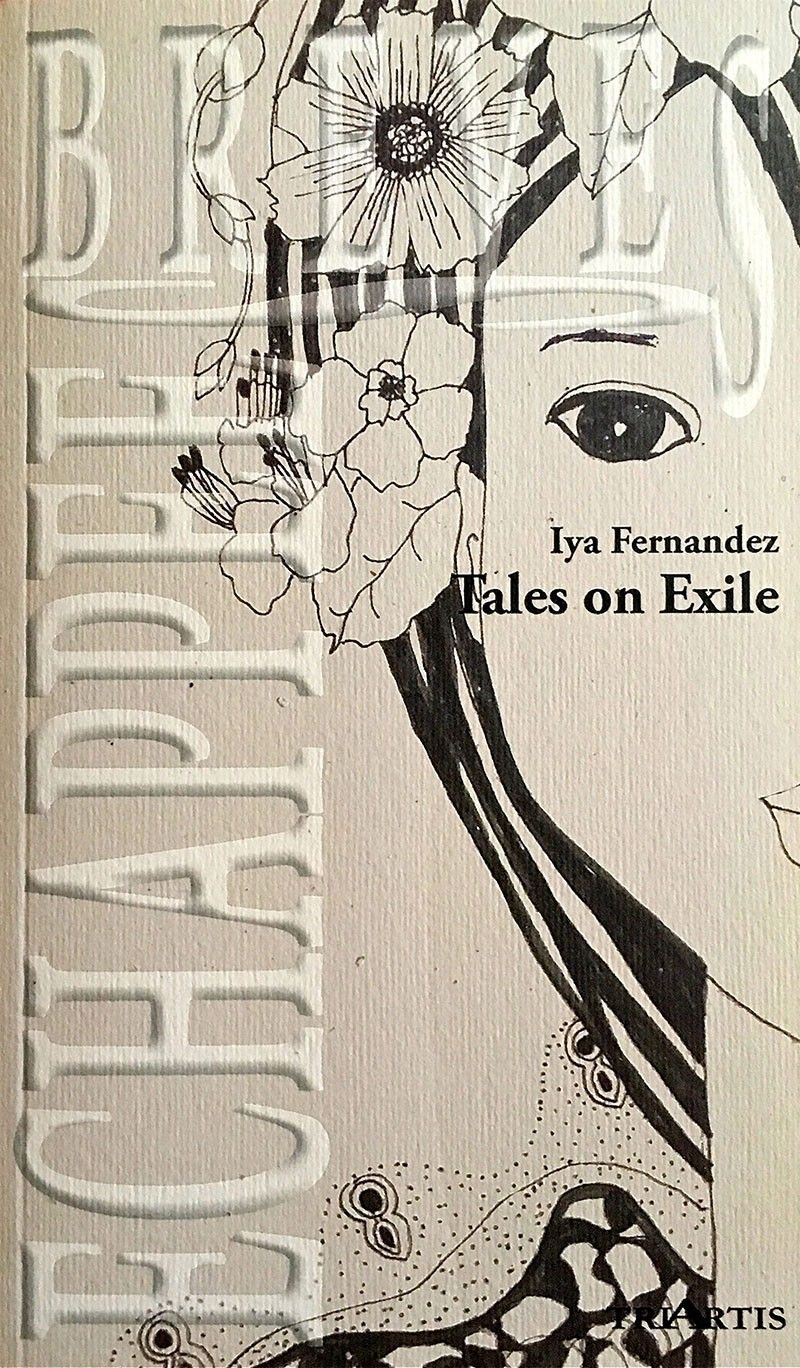

Iya Fernandez’ Tales on Exile is a 50-page book originally published in French in 2015 as part of the Collection Échappés Breves. Now it’s come out in English translation, presumably by the author herself, plus perhaps some friends. It’s published by TriArtis and printed in France, where the author lives — as an artist with a whimsical hand and a delicate touch.

Delicacy of narrative also shines in the nine palm-of-the-hand stories in this collection, which also features several illustrations by the author.

From the back cover text, an excerpt: “In exile, one leaves behind the familiar, one becomes a foreigner in a strange place. There are many kinds of exile, and the reasons one seeks a form of escape may differ. … Nostalgia is imminent and sometimes confusing. Each metamorphosis is not only geographic, but also deeply personal. The characters in this collection have confronted exile in their own way.”

The first story, “Detour,” has a Vietnamese man attracted to the melodious laughter of a lady with a young boy. He follows them from the Paris Metro to a fruit stand where she picks up a pineapple and wonders if she should also get mangoes. When their gazes lock, he realizes that she was the young girl “clinging on to my arm for dear life, her face bathed in tears and brine.”

That was when they were children on a small fishing boat that had sailed from the Baie d’Halong towards the China Sea.

“Our vessel reeked of vomit, death and desperation. The girl held on to me weeping, laughing, losing her bearings, losing her mind.”

Finally rescued at sea, they were brought to the refugee camp in Palawan.

“I then lost track of the girl, but I imagined that she recovered and that she got help to face her traumas and begin again….

“Time had altered our appearance, but she knew me. From one soul to another, we connected briefly. We uttered no words. We were just passing strangers.

“‘Forget the mangoes,’ she said to her son with regret. Then they hurried away with a quick step.”

In “Gardenia,” a 20-year-old Filipina is set to marry a 48-year-old Frenchman who will take her to see the Eiffel Tower. She suggests a roast suckling pig for the reception after the church ceremony.

“There will be a three-layered cake. My cousins will be impressed.

“‘Magdalena, you will soon leave… Please do not forget us,’ they said. Magdalena, dry your tears. You will never grow hungry again.

“My head spins. The scent of gardenia is intoxicating. His kiss was tender, and I felt his desire. I am a gardenia washed by the rain. White, beautiful, fresh.

“Perhaps we will grow to love each other. Perhaps…

“Frederick smiled at me. His silver hair glistens in the sun. If we don’t eat the entire suckling pig, my parents may have some to take home.”

In “The Rose Garden,” Chiquita returns to the husband she left thirty years ago. Their son Kim had long gone off to Australia. Tomas still grows rose bushes and sells the flowers to keep himself and his blind partner Dolores afloat.

“‘Ahh,’ Tomas said with pride in his voice. ‘The roses remain faithful. They stay on the ground, they never leave me.’”

“Rituals” has another abandoned old man whose daughter visits and leaves him a casserole to reheat.

“Chocolate Éclair” has the orphaned art student Solene falling in love with math student Yin, an immigrant in France. She buys éclairs for the boy who may have been distracted by his former fiancée who’s still in Shanghai. But biking back to their flat, she falls and ruins the éclairs that “were in the basket on the handle-bars, in a carton tied with pink ribbon.”

The story’s first paragraph says it all:

“Today I fell off my bicycle and got a few scratches on my knee. Nothing serious, but I sat on the sidewalk and cried.”

“Taking Tatiana to the Botanical Gardens” has another Filipina arriving in Paris with a six-month-old daughter to join her spouse whom she met in Manila. On their second day, the father suggests that she take the child to Jardin des Plants — which she does. The story ends thus:

“I should look up the bird annals of Buffon and Cuvier. The streets alongside are named after them. I read somewhere that migratory birds are happier than sedentary birds. Do you think we are like birds, Tatiana?”

The last three stories are also about people who have been left behind to fend for themselves or are looking forward to start or restart relationships.

“Solitaire” has an unnamed I persona — traumatized by her father’s departure and her mother’s bitterness — wondering if she’s fated to have a solitary life. “Surprises” tells of two orphaned brothers who care for one another, with the story ending on a mysterious note. The saddest is the last, “Tamarind Soup (Sinigang),” where Nenita discovers that her husband has come home from Saudi Arabia but gone straight to another woman. Instead of making a scene, she resolves to continue caring for her three kids and her folks. She cooks sinigang.

In these stories of abbreviated excellence, the sour but hearty broth is welcome. Exile is either sought by or foisted on the characters, while both nostalgia and expectations are limned with ironies that are also objective correlatives for alienation.

A roast suckling pig, rose bushes, a casserole, ruined éclairs… They’re topped off by the wedding dress Nenita and her mother are asked to sew. It will help the family’s unstable coffers.

“… Isn’t that great? This is the beginning of good things.

“Nenita forced a smile and tried to show her mother some enthusiasm. A wedding dress. How lucky we are. She then began cooking, and not long after the house was filled with the sweet scent of tamarind soup.”

This slim book on stout spirits will be available soon at

Leaving the familiar behind

KRIPOTKIN Alfred A. Yuson

Iya Fernandez’ Tales on Exile is a 50-page book originally published in French in 2015 as part of the Collection Échappés Breves. Now it’s come out in English translation, presumably by the author herself, plus perhaps some friends. It’s published by TriArtis and printed in France, where the author lives — as an artist with a whimsical hand and a delicate touch.

Delicacy of narrative also shines in the nine palm-of-the-hand stories in this collection, which also features several illustrations by the author.

From the back cover text, an excerpt: “In exile, one leaves behind the familiar, one becomes a foreigner in a strange place. There are many kinds of exile, and the reasons one seeks a form of escape may differ. … Nostalgia is imminent and sometimes confusing. Each metamorphosis is not only geographic, but also deeply personal. The characters in this collection have confronted exile in their own way.”

The first story, “Detour,” has a Vietnamese man attracted to the melodious laughter of a lady with a young boy. He follows them from the Paris Metro to a fruit stand where she picks up a pineapple and wonders if she should also get mangoes. When their gazes lock, he realizes that she was the young girl “clinging on to my arm for dear life, her face bathed in tears and brine.”

That was when they were children on a small fishing boat that had sailed from the Baie d’Halong towards the China Sea.

“Our vessel reeked of vomit, death and desperation. The girl held on to me weeping, laughing, losing her bearings, losing her mind.”

Finally rescued at sea, they were brought to the refugee camp in Palawan.

“I then lost track of the girl, but I imagined that she recovered and that she got help to face her traumas and begin again….

“Time had altered our appearance, but she knew me. From one soul to another, we connected briefly. We uttered no words. We were just passing strangers.

“‘Forget the mangoes,’ she said to her son with regret. Then they hurried away with a quick step.”

In “Gardenia,” a 20-year-old Filipina is set to marry a 48-year-old Frenchman who will take her to see the Eiffel Tower. She suggests a roast suckling pig for the reception after the church ceremony.

“There will be a three-layered cake. My cousins will be impressed.

“‘Magdalena, you will soon leave… Please do not forget us,’ they said. Magdalena, dry your tears. You will never grow hungry again.

“My head spins. The scent of gardenia is intoxicating. His kiss was tender, and I felt his desire. I am a gardenia washed by the rain. White, beautiful, fresh.

“Perhaps we will grow to love each other. Perhaps…

“Frederick smiled at me. His silver hair glistens in the sun. If we don’t eat the entire suckling pig, my parents may have some to take home.”

In “The Rose Garden,” Chiquita returns to the husband she left thirty years ago. Their son Kim had long gone off to Australia. Tomas still grows rose bushes and sells the flowers to keep himself and his blind partner Dolores afloat.

“‘Ahh,’ Tomas said with pride in his voice. ‘The roses remain faithful. They stay on the ground, they never leave me.’”

“Rituals” has another abandoned old man whose daughter visits and leaves him a casserole to reheat.

“Chocolate Éclair” has the orphaned art student Solene falling in love with math student Yin, an immigrant in France. She buys éclairs for the boy who may have been distracted by his former fiancée who’s still in Shanghai. But biking back to their flat, she falls and ruins the éclairs that “were in the basket on the handle-bars, in a carton tied with pink ribbon.”

The story’s first paragraph says it all:

“Today I fell off my bicycle and got a few scratches on my knee. Nothing serious, but I sat on the sidewalk and cried.”

“Taking Tatiana to the Botanical Gardens” has another Filipina arriving in Paris with a six-month-old daughter to join her spouse whom she met in Manila. On their second day, the father suggests that she take the child to Jardin des Plants — which she does. The story ends thus:

“I should look up the bird annals of Buffon and Cuvier. The streets alongside are named after them. I read somewhere that migratory birds are happier than sedentary birds. Do you think we are like birds, Tatiana?”

The last three stories are also about people who have been left behind to fend for themselves or are looking forward to start or restart relationships.

“Solitaire” has an unnamed I persona — traumatized by her father’s departure and her mother’s bitterness — wondering if she’s fated to have a solitary life. “Surprises” tells of two orphaned brothers who care for one another, with the story ending on a mysterious note. The saddest is the last, “Tamarind Soup (Sinigang),” where Nenita discovers that her husband has come home from Saudi Arabia but gone straight to another woman. Instead of making a scene, she resolves to continue caring for her three kids and her folks. She cooks sinigang.

In these stories of abbreviated excellence, the sour but hearty broth is welcome. Exile is either sought by or foisted on the characters, while both nostalgia and expectations are limned with ironies that are also objective correlatives for alienation.

A roast suckling pig, rose bushes, a casserole, ruined éclairs… They’re topped off by the wedding dress Nenita and her mother are asked to sew. It will help the family’s unstable coffers.

“… Isn’t that great? This is the beginning of good things.

“Nenita forced a smile and tried to show her mother some enthusiasm. A wedding dress. How lucky we are. She then began cooking, and not long after the house was filled with the sweet scent of tamarind soup.”

This slim book on stout spirits will be available soon at Amazon.com.