From a fine novel to a fine film

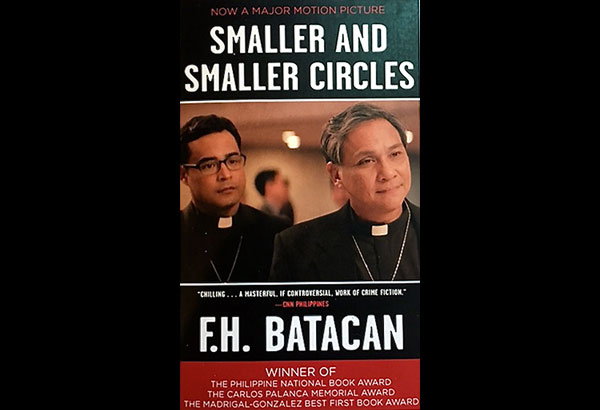

To have an excellent local novel turned into an excellent local film is no less than heartening. The long journey taken by F.H. Batacan’s Smaller and Smaller Circles, written as a novella nearly two decades ago, and first published by UP Press in 2002, is well worth the wait.

Dubbed as our country’s first crime novel — highly ironic given our climate of incessant crime — as a manuscript it won the Palanca Grand Prize for the Novel in English in 1999, then the Madrigal-Gonzalez Best First Book Award in 2002, and the Manila Critics Circle’s National Book Award in 2003.

The laurels could’ve ended there, but as “Ichi” Batacan’s literary merit and pluck would have it, her book caught the attention of a US publisher. She was asked to expand the story, which Ichi had already set on doing, despite her decade-long professional engagement as a news producer in Singapore. The result was the Soho Press edition released in 2013, which nearly tripled her original word count of 40,000 words.

A couple of Jesuits — forensic anthropologist Fr. Guz Saenz and his younger protegé Fr. Jerome Lucero — are asked to help the NBI with detective work on a series of gruesome murders on adolescents in a shanty area, with their mutilated bodies recovered in the Payatas dump site.

They go up against the long-held premise that a Catholic country with strong family and community relations, inclusive of an inordinate gossip level, can’t have serial killers. Given his own experience with police work, Fr. Saenz’s musings attribute the source of the prevailing misimpression to bureaucratic inefficiency and sloppy record-keeping.

Meanwhile, his more important frustration has to do the predatory conduct of a Monsignor Ramirez who handles charity funds. Despite Fr. Gus’ complaints to higher Church officials, the molester-in-robes just keeps getting transferred parish-wise, while the protective Cardinal Meneses dismisses the rational contention that it would be “better dealt with in the cleansing light of transparency and openness rather than in the darkness of secrecy.”

These parellel sets of urban predators are the demons or “bad guys” that Fr. Saenz and Fr. Lucero have to bring to light, and hopefully to heel. Standing in their way are archetypal characters such as Cardinal Meneses and NBI sub-alterns seeking to unseat Director Lastimosa, the Jesuits’ ally as the rare government official who abides by righteous principle.

The book is such an engaging read, a page-turner that benefits from a solid narrative structure, memorable characters, situations and contretemps that hold up an authentic mirror to Philippine society, crisp dialogue, well-rendered back stories, and personal ruminations, including those of the killer (whose own early history of having suffered from abuse triggers his crimes).

Converting all these to the screen is obviously quite a challenge. Screenwriters Ria Limjap and Moira Lang and director Raya Martin are happily up to the task, albeit the usual problems of excision and compression take a minor toll.

Some peripheral characters are understandably done away with, or depicted rather differently from the book. The TV news producer Johanna Bonifacio, another ally on the side of truth, is given a larger role, while her collaborative spunk is enhanced with eye-candy quality.

The hefty Rommel Salustiano who serves as the initial red herring in the book has his role diminished into a single scene in the movie. Taking his place as the film’s red herring is a Dr. Gino, the main dentist in a mobile clinic, who was a lady in the book. Conversely, Councilor Mariano becomes a lady.

Changing the threatening communication from the killer —from a mailed empty envelope with tell-tale signs to a more cinematic jar that suddenly finds itself on Fr. Gus’ lab shelves — is also acceptable, as it compresses the scene and its import. But it immediately follows a lengthier expository sequence, making it too crunched up in the narrative arc that leads to the killer’s identification.

The climactic confrontation in the mobile clinic also gives way to a more cinematic setting — a large empty building where Fr. Gus can ratchet up the suspense by trodding a mile through dark corridors. But it also raises the question of how the NBI and police officials can allow him to confront the killer alone, while they remain distantly removed from possible quick rescue.

The manner of the killer’s demise is significantly altered, saving the police from further ill repute for yet another bungled job. This last part finds the narrative questionably disturbed, with hopscotch crosscutting between the killers’ parents speaking to Fr. Jerome while a late-appearing Emong confides with Fr. Gus. Thus, the consequences set in motion by another child abuser, the P.E. teacher Gorospe, seem to be revealed too late. Non-linear editing can only manages to depict Gorospe’s grisly comeuppance as a befuddling scene.

In the seeming rush to build up to a climax and subsequent coda, the character of Director Lastimosa, deeply etched in the novel, is suddenly given short shrift, so that he disappears after his last favorable action.

Now, before I get charged with nitpicking in favor of the book’s original narrative chronology, let me say that I found the film gripping in its own right. The cimematography by JA Tadena is outstanding, as are the music by Lutgardo Labad and production design by Ericson Navarro. The performances are generally above par, paricularly those of Nonie Buencamino as Fr. Saenz, Carla Humphries as Joanna, Ricky Davao as Cardinal Meneses, Raffy Tejada as Atty. Ben Arcinas, and TJ Trinidad as Deputy Jake Valdez.

Screenwriters Limjap and Lang preserve the original dialogue in English verbatim, and where they add new scenes and lines, these turn out creditable more than simply functional. The young director Raya Martin is evidently masterful with noir filmmaking. He handles the ensemble just as masterfully.

I must say however that I found the early going to be too talky and static, bereft of dynamic pacing. It only picks up eventually. And what a long tracking shot can do, when Fr. Gus and Fr. Jerome are guided through the parish’s feeding center. On the other hand, after first meeting Joanna on a stairwell, they remain in their positions through so much more dialogue. This particular stasis is redeemed much later when the raiding police team ascend another, more cinematic since spiral staircase.

While the back stories and silent ruminations are necessarily truncated, there might have been a way of incorporating Fr. Gus’ trenchant observations, such as how weathy matrons involved in charity work are more concerned with where their money goes than how the monsignor who handles these funds takes advantage of minors.

Still and all, it’s a brave and successful effort to transpose a fine novel into a fine film. It had its premiere on Dec. 2, and will start regular screening on Dec. 6. I’m rooting for a grateful, intelligent audience. The movie tie-in edition of the book is available in NBS branches. I’m hoping for more readers, too.

Indeed, as the memorable character of Fr. Saenz postulates, serial killings are quite commonplace in our excessively crime-prone country. Why, we might even say Jesuitically that there’s this dark overlord of an instigator behind current serial murders. But then that’s another psychological thriller of a story.