In the afterglow

As many of you know by now, in the early hours of April 1, a Friday, the UP Faculty Center went up in smoke. I was playing poker at my usual haunt, the Metro Card Club in Pasig, when I got a flurry of text messages from Krip Yuson, who had just heard of the fire on Facebook. Distraught, Krip sent me pictures of the unfolding scene — flames were billowing out of the FC’s upper floors, and it was clear that nothing and no one could possibly survive such a catastrophic event. I thanked Krip for the heads-up, put my cards down, and drove off to UP to see the fire for myself.

We live on campus, in a faculty bungalow on Juan Luna Street, a 10-minute walk from the FC, so UP was literally home for me. But I also held office at the FC, in the English Department, and the FC had been my official address for over 30 years since I began teaching in 1984. As I drove to Diliman I thought of my room, FC 1036, which I had had to myself since I came home from graduate school in 1991; before that, I’d shared FC 1012 with the late Angelito Santos and Ernie Bitonio, who became a lawyer and labor official.

The English department burns.

Anyone who’s studied at UP Diliman would have gone through the FC at one point or another, and the place was rife with tales not only of intellectual and political adventure, but also of mischief of a baser, if more entertaining, nature. My favorite one, possibly apocryphal, had to do with an eminent lady professor going out on the window ledge and hanging on for dear life to spy on a neighbor whom she suspected of having an assignation with a student. Another hand-me-down scene involved two feuding scholars — one delivering a professorial chair lecture in CM Recto Hall while her nemesis handed out a vitriolic flyer at the door to anyone coming in.

It’s funny how the tragic can provoke the comic — and the professorial life certainly doesn’t lack for evidence of human frailty and folly — but it’s as good a response as any to personal loss, which was what the FC fire was really about. True, we lost a campus landmark and an academic institution. But buildings can be rebuilt — and the half-century-old FC was long overdue, anyway, for a massive renovation.

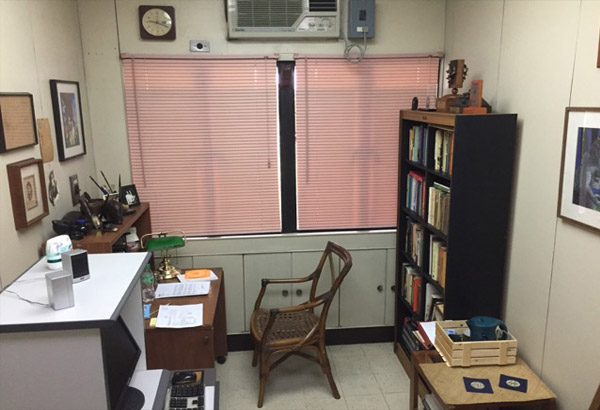

The FC’s subdivision into departments and then into individual rooms and cubicles guaranteed that each little corner would become treasured (and jealously guarded) personal space — not just mini-offices but mini-libraries and mini-galleries, showcases of both tradition and individual talent. Aside from the usual family pictures and diplomas (of which I actually saw precious few on display, perhaps in tacit admission of the silliness of flaunting one’s PhD in a boatload of them), shelves full of precious books and walls hung with choice art described the typical FC room, and each room’s state of order or chaos indelibly imprinted the tenant’s character on the visitor’s mind.

In UP, with historically low salaries and precious few incentives, a room of one’s own is an earned privilege. Professors are kings, and their offices are their castles and citadels, open to students and colleagues but impregnable to the unwelcome (except during martial law, when the military marched into the FC willy-nilly in search of Redheads). During the Diliman Commune in 1971, we’d renamed the place “Amado Guerrero Hall,” after the nom de guerre of Joma Sison, who had been an instructor with the English department.

My office in better times

Once aflame with revolution, now it was literally on fire, and three hours after the fire began, I watched as an eerie orange glow illuminated its interior. The text messages had shown tongues of fire curling out the windows, but the blaze had mellowed down a bit when I got there. Had I arrived at its peak, I would have been too excited to feel pain, but its muted state invited contemplation, which invited melancholy. I stood outside the building facing our department, facing my corridor, and understood that very little, if anything, would survive. (And of course the scene was not without its black — or should I say its blackened — humor; I overheard an exhausted fireman asking, “Does anyone have a cigarette?” I can’t write this account without thanking the dozens of firemen from all over who battled that inferno — you all deserved a good puff afterward.)

As my fellow FC denizens would do in the coming days, I began taking stock of what I was losing even as I watched: a Joya nude (one of two that Beng had saved from her days at Fine Arts; thankfully we had given one to our daughter Demi); a large giclée print of lilies gifted to us by Jaime Zobel; two paintings we had bought from a young Jason Moss; a National Book Award trophy by Agnes Arellano in the shape of a typewriter, my favorite among all my illustrious paperweights; my TOYM trophy by Napoleon Abueva, which, meaning no disrespect, did double duty as a hat rack; two of Beng’s serene waterscapes, which I had commandeered from her exhibitions; and a drypoint portrait that I had made myself (in another life as a printmaker) of her whom I was yet courting.

There were the books: among many others, a first edition of Without Seeing the Dawn, signed by its first owner, the novelist Zoilo Galang; a signed copy of Villa Magdalena by Bienvenido Santos; more first editions of NVM Gonzalez, Nick Joaquin, and F. Sionil Jose; and a copy of Ninoy Aquino’s prison testament, which Cory Aquino had signed and gifted to me in thanks for some speeches I had happily done for her pro bono.

And then of course there were my own books and papers — file copies of nearly all my books, and assorted publications, including 20 copies of the first printing of Penmanship, whose special paper I treasured and therefore hoarded; and my only copy of my dissertation. Luckily I had left only one of my fountain pens in the office, a Conklin desk set from around 1925, and a handsome crystal inkwell from Barcelona. Most of these could be replaced, but not the letters of friends and students over 30 years, nor the cane chair handmade by my late father in law, on which I took many a siesta.

In the end, I found myself mumbling, “It’s all just things,” but of course it wasn’t. Men don’t grieve well, and over the next few days I grew increasingly sullen and irritable. Last Monday I joined a supervised foray into the burnt-out premises, just to see what we could recover. Almost everything we knew and owned had turned to mounds of char, which remained warm and smoky beneath our booted feet. From my blighted corner I picked up a ceramic mug that had lost its bottom. I also rescued a porcelain guan yin that belonged to Jing Hidalgo, and the ravaged hulk of a Royal typewriter I had given Isabel Mooney two decades earlier. We staggered out with our loot, laughing, and then the desolation hit us.

My grandmother Mamay used to sing us a lullaby which Ilonggos will recognize, about how life and sweet things will simply drift up and away in bitter smoke, and that weekend some of that life and some of that sweetness rose up into the air.

“We Pinoys are disaster-proof,” I tweeted at some point, mindful of how small our plaints seemed compared to a Yolanda. I do believe that, and we literary types have probably used up all our phoenix metaphors in the fire’s afterglow. But I’ve also always believed in proper goodbyes, so before we haul in the new furniture into the inevitable new FC, here’s mine, to ash-covered memory.

* * *

If you want to tour the aftermath of the FC fire with me, see the video here: https://youtu.be/ER1co3z-lGg.

Email me at penmanila@yahoo.com and check out my blog at www.penmanila.ph.