Lilas offers misty-eyed look at ‘golden ages’ of Cebuano cinema

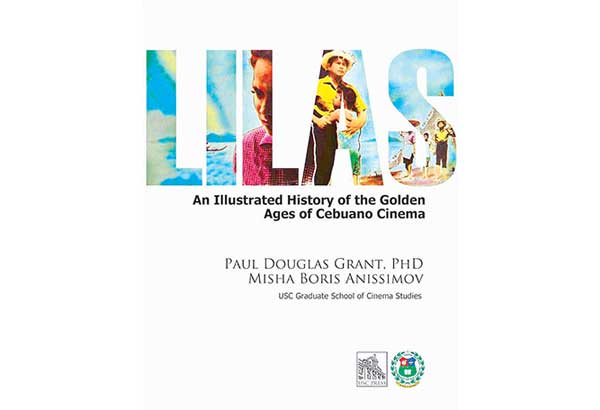

In Lilas: An Illustrated History of the Golden Ages of Cebuano Cinema, the glory days of Cebuano cinema in the ‘50s and ‘70s are retraced through visual imagery and archival research that took the authors, Dr. Paul Douglas Grant and Prof. Misha Boris Anissimov, three years to complete.

MANILA, Philippines — Patay Na Si Hesus, Ang Damgo ni Eleuteria and Confessional are some of the more notable Cebuano films in the last decade that cut through language and cultural barriers, among others, to make an impact in what has been oft-described as a (still) very Manila-centric movie industry.

The 264-page coffee-table book Lilas: An Illustrated History of the Golden Ages of Cebuano Cinema, however, will tell you that preceding these films is a long and colorful history perhaps largely unknown to the younger generation. It’s a veritable collector’s item that any earnest student or fan of Filipino cinema should consider having.

Lilas is a collaborative project of two authors — Dr. Paul Douglas Grant and Prof. Misha Boris Anissimov, who are both connected with the University of San Carlos Graduate School of Cinema Studies.

Published by the University of San Carlos (USC) Press and distributed by Soline Publishing Company, Inc., Lilas was launched late last year in Cebu. We were able to get a copy of the book (special thanks to Dr. Jobers Bersales, manager of the USC Press and Nikki Oguis, business unit manager of Soline Publishing) after the recent Manila International Book Fair where Soline was one of the exhibitors.

In the introduction, the authors wrote that the book doesn’t claim to offer an encompassing account of the history of Cebu cinema but at the very least, provide “a brief overview of the major touchstones up to the time of the writing of this book.”

The so-called golden ages of Cebuano cinema are retraced through visual imagery, memories of “former spectators” and archival research that took Grant and Anissimov three years to complete.

As per the authors’ description, Lilas is a “heavily illustrated book” featuring old movie ads, news clippings and comics which will surely evoke a sense of nostalgia among those who have “vague recollections of what the ephemera of this cinematic tradition looked like.” And for those belonging to the younger set, it’s always nice to look at the past to see how far things have gone.

Some of the interesting trivia you’ll read from the book: the ’50s and the ‘70s were two busiest periods of Cebuano cinema.

While the book discussed that there was already a “rich history of cinema culture in Cebu” before World War II — Bertoldo ug Balodoy, considered first Cebuano film, was made in 1939 — it also noted that the post-war period served as the first real era of “consistent” Cebuano language feature filmmaking.

So, just how “golden” or prolific was this period? During this time, the island-province saw the highest number of films made in the classical (a.k.a. pre-digital) mode of production. Citing a dossier on Cebuano cinema by eminent historian Dr. Resil Mojares, the book said that a total of 80 Cebuano films were produced from 1947 to 1960.

The authors also wrote that in 1951, the National Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences opened in Cebu and offered film education. The academy was run by a certain Rudy Robles, a US army lieutenant and a Hollywood actor.

The early ‘50s introduced such Visayan stars such as Gloria Sevilla and Mat Ranillo Jr. who first acted together in the film Princesa Tirana. They would become husband and wife, and touted as the King and Queen of Visayan movies.

Lilas also chronicled the second golden age — from around 1973 to 1975 — that happened despite, as the authors noted, “the absence of a film distribution infrastructure” and back-dropped by political uncertainty and the imposition of the Martial Law.

Over 30 Cebuano films were made by a mix of Cebuano-owned and Manila-based production companies, and participated in by Cebuano and Tagalog directors, talents and crew that it “was a seeming gold rush to capitalize on a perceived underserved Visayan-speaking market.” These included the Manila-based Magnolia Pictures which produced successive Cebuano language films. During this time, there was also an attempt to develop a star culture in Cebu, giving rise to the likes of Chanda Romero and Pilar Pilapil.

The book credited a few films for somewhat ushering in this second wave. One was Badlis sa Kinabuhi (1969) starring Mat Jr. and Gloria, which was described as “steeped in local film lore as a canonical example of Cebuano cinema.” Gloria’s character is a rape victim who, out of self-defense, kills her attacker/stepfather, but is consequently scorned by her husband (Mat Jr.) after the incident.

Lilas detailed how after the release of the film, in September of 1969, Mat perished in a plane crash. The widowed Gloria then brought her Visayan films to Manila. In 1979, Badlis received high recognition including FAMAS awards for the actress. The film was also exhibited in Berlin. The authors further wrote that the success of the film helped foster a “sense of renewed confidence in Visayan cinema” among the members of the local film community, which in turn, led to a new and eventful chapter in the industry.

After that period, the book noted that the film wave collapsed. However, one film in 1977 proved that a “movie made by and made for Cebuanos” could be commercially viable. Ang Manok Ni San Pedro, which was based on a radio drama, shot with a super 8mm by businessmen Narciso and Domingo Arong and exhibited in fiestas, became a blockbuster, “reportedly busting wide open all existing box-office records for Tagalog and Visayan movies.”

The authors wrote that the film showed that the “Visayan potential of a complete production-distribution-exhibition model independent of the Manila film establishment.”

As written in the book, Cebuano films during these glory days were inspired by or adapted from pop culture — from stage plays, musical plays, radio programs to comic serials, among others. Some of the comic serials like Batul of Mactan and Ang Medalyon nga Bulawan are reprinted in full color in the end section of Lilas.

Some more interesting information from the essays include the story behind the controversial first Visayan Film Festival in the ‘70s, as well as the journalistic (both positive and dismal) observations and ruminations about the past, present and future of Cebuano film industry. “Dead as a doornail,” as one read. But hope floats as the book touches on how new works from a new breed of filmmakers — such as Jerrold Tarog and Ruel Antipuesto’s Confessional (2007 Cinema One Originals Best Picture) and Remton Zuasola’s Ang Damgo ni Eleuteria (2011 Gawad Urian Best Picture) — have cropped up, many thanks to digital technology.

Through the book, you’ll have a sense of how much has changed and how much has remained — like issues and challenges faced then and now — maybe not just in relation to Cebuano cinema, but the Philippine movie industry as a whole. And so the story of Cebuano cinema continues.

(For inquiries on how to order the book, email [email protected])

- Latest

- Trending