Vintage paperback faves

The recent theatrical screening of the animation film Loving Vincent brought me all the way back to the early 1960s when as a teenager I consumed fast hours devouring paperbacks purchased either from Alemar’s on Avenida Rizal or the stand-alone book stalls spread around the area.

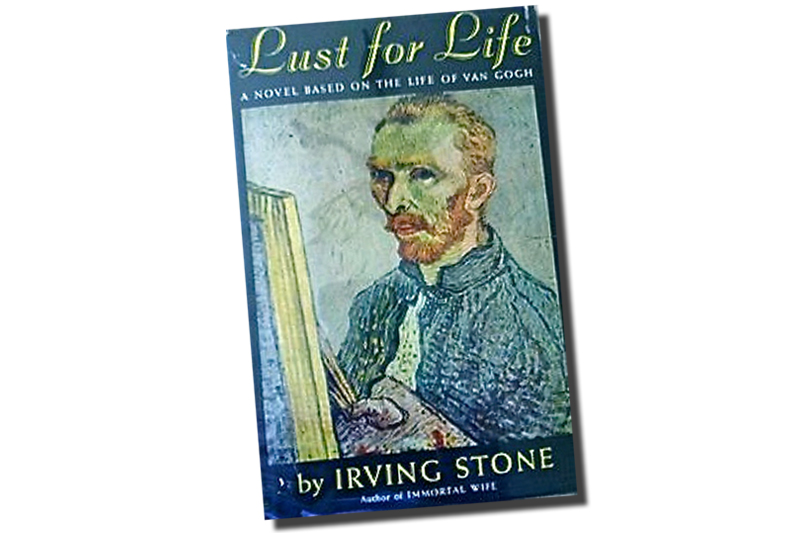

One of these was Lust for Life by Irving Stone. I finished the thick page-turner in a couple of days, so thoroughly and emotively engaged was I with the engrossing if sad tale of the ill-starred Impressionist painter Vincent Van Gogh — his bouts with depression and delusion, tempestuous partnership with Paul Gauguin and their dalliances with brothel denizens, and above all, the Dutch painter’s memorable correspondence with his loving younger brother Theo.

Stone’s description of the quality of light in Arles in southern France had me just as intoxicated. I thrilled to the change of palette from Vincent’s initial dark depictions of “The Potato Eaters” to his sun-blessed “Sunflowers” series. I was both pained and awed when he cut off an ear and offered it to a prostitute.

At the time, I was an innocent, voracious reader, with bohemian lifestyles and unconventional rebels ushering me into worlds of fascination. Juvenile imagination was entirely tabula rasa, ready to appreciate all romanticized narratives, unlike much later when a measure of literary sophistication condemned one to the purgatory of critical appreciation.

But my instincts regarding paperbacks were frequently spot-on. Stone’s 1934 debut novel had become both a critical success and a bestseller, and was turned into a fine movie starring Kirk Douglas in 1956. Directed by Vincente Minnelli, it won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor Anthony Quinn who played Gauguin.

Come to think of it, most of my reading fare were novels that were turned into popular movies. Another was Willard Motley’s 1947 bestseller, Knock on Any Door — on Chicago hooligan Nick Romano’s dramatic trial for murder of a police officer. His motto resonated in my impressionable mind: “Live fast, die young, and have a good-looking corpse.”

I finished it in one sitting, then had the good fortune weeks later of catching the 1949 film noir version at the triple-fare Palace theater. Directed by Nicholas Ray and starring Humphrey Bogart as Nick Romano’s courtroom defender, it was just as riveting. The young John Derek played Nick, whose sentencing to the electric chair fulfilled his rebellious battlecry.

Yet another fave was Alan Le May’s The Searchers, a doorstop of a Western epic published in 1954 and made into an equally classic movie two years later by the eminent director John Ford, starring John Wayne, Jeffrey Hunter and Natalie Wood.

This historical fiction told in the grand manner remains memorable. It’s a lengthy account of how two men, the grizzled Texican Amos (who inexplicably becomes Nathan in the movie) and the idealistic younger Martin spend a decade of frustration tracking down a Comanche band that had massacred their family relations and made off with a young girl, Amos’ niece Debbie.

Their search for her eventually turns climactic when they realize she had been turned into a squaw. But even before they find her and exact retribution on the Comanches, Martin had slowly recognized Amos’ determination as having nothing to do with saving the young woman. He had secretly been in love with her mother, his sister in law, and all he had in mind was revenge. Martin, who had been adopted by the family, still regarded her as a long-lost sister. He stands up to Amos/Nathan in the gripping climax.

The scene is just as terrific in the film, when Jeffrey Hunter shields Natalie Wood from John Wayne’s intent to also gun her down and erase all memory of the Comanche raid. Idealism and bravery win out when the older man grudgingly backs down from another gunfight, and agrees to take his still-beloved niece (despite her having become “Comanche leavings”) back home.

I must have seen the movie a dozen times, and not just because I had irretrievably fallen in love with Natalie Wood. It remains one of my favorite film classics, owing to masterful direction, ensemble acting, cinematography, and a soaring musical score. And even if it took me sometime to accept the usual film abridgement that left out large chunks of the peripheral adventures that marked time for the searchers.

It was the same experience with James Jones’ debut novel, also a doorstop, From Here to Eternity, published to much acclaim in 1951, winning the National Book Award and eventually being named as one of the 100 Best Novels of the 20th century.

Fred Zinnemann turned it into a classic film in black-and-white in 1953. It won eight Academy Awards, including one for supporting actor Frank Sinatra. Apart from being acknowledged as the movie that saved Sinatra’s floundering career, it is often remembered for the iconic Oahu beach scene where Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr frolic sexily in the surf. (No, it wasn’t why the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.)

Well, it’s also memorable for the sensitive performance of soul-eyed Montgomery Clift, as Private Robert E. Lee Prewitt or “Prew,” a bugler and former boxer around whom the central story revolves. And the villainous Ernest Borgnine as Sgt. Fatso Judson, whom Prew engages in a knife fight to avenge his buddy Pvt. Angelo Maggio’s death.

In the book, it’s not Maggio (Sinatra) whom Prew avenges, but another character he’s befriended while in Fatso’s stockade. Again, large chunks of the epic narrative are dropped from the movie, including the grittily detailed stockade scenes.

One scene I was glad to see retained was that of Prew playing a tearful Taps on his bugle when Maggio dies, with the entire camp rapt in attention. James Jones rendered this in deathless prose, describing how Taps’ three basic notes could hold one in thrall even when played by a single bugle.

Well, all of that paperback reading meant such rewards that uplifted the spirit and taught lessons in imaginative storytelling and the crafting of effective prose. And it all climaxed when I was 16 and picked up my copy of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, where the opening passage transported me further into a life of lusting and fascination, not necessarily in that order.

“Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta. She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita….”

From the novel’s publication in 1955 to Stanley Kubrick’s original film version in 1962 was a good seven years, but it certainly wasn’t one of arrested development for this paperback reader.